Stories of Communist Education: Part I

Amid rolling hills, green pastures, the grand Carpathians and their forested winding roads littered with countless bears, sheep, and shepherds, lies the beautiful country of Romania. The medieval charm of the Moldovia region in the East, the Art-Nouveau and German architecture in Transylvania and the West, and the Capital—or “Little Paris—” near the Black Sea in the South all make up only part of this beautiful country. But within these regions lie stories of struggle and strength of a people still fighting to heal the nation from years of despotic control.

In these past few months, I have undertaken a quest to understand what it was like to be educated in Romania under communist rule—the good, the bad, the beautiful, the ugly. I have a special connection to this woodland of castles and cathedrals. My father was born in the countryside of Cluj, and my mother in the city of Timișoara, meaning they are both from around the famous, or should I say infamous, Transylvania—the region of Dracula (Vlad the Impaler).

“Castelul Bran,” or Dracula’s Castle (if you’re a fan) Dobre Cezar under CC BY-SA 3.0.

After World War II, Romania—primed by various internal communist groups and Moscow-trained intellectuals—elected its first communist dictator, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, who laid the groundwork for his notable successor, Nicolae Ceaușescu. This notorious Romanian dictator became the General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party in 1965, and he remained so until 1989, when he and his wife, Elena, were publicly executed after the people of Romania gathered in rebellion against his rule. Initially, he maintained the status quo with a relatively standard grip over the country as he followed the example of Gheorghiu-Dej’s rule. However, early on, Ceaușescu showed signs of change as he was willing to play nice with America by displaying a veneer of a free and prosperous Romania to gather as much financial support as possible.

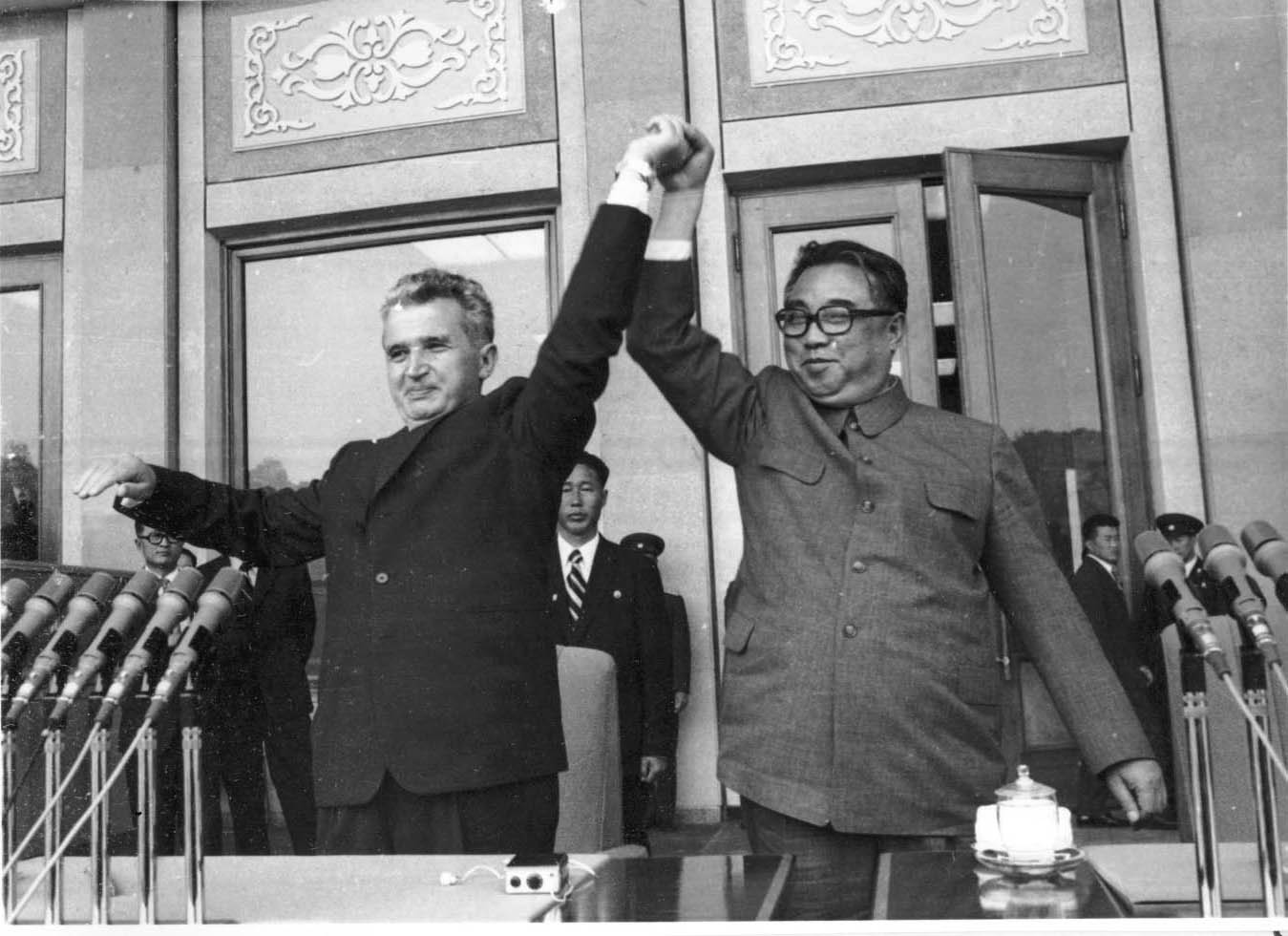

It was really in 1971 when Ceaușescu visited North Korea that communism in Romania dramatically began to worsen. It is safe to say that Ceaușescu, the shoemaker to communist dictator, was entirely enchanted and emboldened by Kim’s cult of personality layered with grandiose displays of wealth and power. During his visit, Ceaușescu and his wife were treated like gods by Kim Il Sung and his people, who he had gathered in grand synchronized assemblies to greet and sing to the Ceaușescus soon after their arrival. This warm welcome and detailed introduction to North Korean affairs left Ceaușescu bursting with fantastical visions of what could be done throughout his time ruling Romania. He returned and delivered a speech now known as the “July Theses,” which commanded the implementation of increasingly radical cultural, political, and academic reform in the name of Ceaușescu’s brand of communism.[i]

Ceaușescu (left) and Kim (right) enjoying each other’s company (1978). This image is available from the Romanian Communism Online Photo Collection under the digital ID 44994X6X, #BA393, Fototeca online a comunismului românesc, (08.29.2025), ANIC, ISISP archival database, 163/1978.

Years after Ceaușescu’s trip, and as another result of his desire to emulate the philosophy and actions of Kim, Ceaușescu initiated the construction of the infamous Palatul Poporului or “The People’s Palace.” For reference, this gargantuan palace, now the capital building, is currently the largest functional parliament building in Europe.[I] Ceaușescu’s mind was set on manufacturing glory no matter the cost although he never lived to see the palace fully built. Despite its title, the palace’s name is a misnomer built in the people’s name when, in reality, it was anything but. The project led to the displacement of over 50,000 people and the appointment of 100,000 laborers. It drained resources from every region of Romania while the country’s people suffered—all this amounted to a grand toll. Thousands of Romanians died while working to build the decadent People’s Palace.[ii] Before Ceaușescu initiated the project, the Romanian people were already struggling to survive, eat, and provide warmth for their families with the small number of resources allowed to them by the communist government. All the while, Ceaușescu hoarded more of the country’s supplies to build his palace and to complete his mission of paying off the country’s debt through exports. As a result, the weight of poverty and famine smothered the people.

Nicolae (middle) and Elena (left) while visiting the collective farm in Târgu Mureș that Alin (not pictured) worked on. This image is available from the Romanian Communism Online Photo Collection under the digital ID 35222X16X19, #L088, Fototeca online a comunismului românesc, (08.29.2025), ANIC, ISISP archival database, 88/1979.

But what was everyday life like for the Romanian people during this time? What was the lot of all those men, women, and children who were never employed to build the palace but still trapped under the yoke of the Socialist Republic of Romania?

The stories of a few of these Romanians are some of the most memorable of my early years. I grew up hearing of the hardships my grandparents had to overcome to make it to America as they risked imprisonment and came near death at the hands of the secret police, or Securitate, during Ceaușescu’s last years of power in the 1980s. These tales and my grandparents and parents who lived to tell them have shaped me in ways I cannot even begin to count; the family history is forever drilled into my brain, and I keep learning more. Upon this foundation lies the basis for my further inquiry into the Romanian communist school system. So, what was the Romanian education like?

To find out, I prepared twenty-one questions to ask various interviewees about the conditions and philosophies that undergirded the society and culture of Romanian communism. Some of the individuals I interviewed in pairs as they were married couples, while others I talked to individually. The participants were of varying ages, born somewhere between 1949 and 1977; they went on to study and work in various fields. Although their circumstances were diverse, all the interviewees were educated for some time under the communist regime.

What follows are the tales of eleven Romanians born into a communist system they had no part in establishing.

[1] STANCIU, CEZAR. “THE END OF LIBERALIZATION IN COMMUNIST ROMANIA.” The Historical Journal 56.4 (2013): 1063–1085. Web.

[2] Palace of the Parliament Rolandia: Your local expert for Romania. Available at: https://rolandia.eu/en/blog/places/palace-of-the-parliament?srsltid=AfmBOoq8xDqEOuSJv5ZVzuXCQS4pzq2vrAWrGyrVtFm_MYfG5kaRuMnw (Accessed: 02 May 2025).

[3] Service, R.R. and Despa, O. (2024) Ceausescu’s Grand Vision: A legacy built on rubble, RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Available at: https://www.rferl.org/a/ceaucescu-s-grand-vision-a-legacy-built-on-rubble/33066370.html (Accessed: 02 May 2025).

This image is available from the Romanian Communism Online Photo Collection under the digital ID 44226X4983X5732, #V126, Fototeca online a comunismului românesc, (08.29.2025), ANIC, ISISP archival database.

Deniza Toma, an Arizona native, recently earned a Master’s degree in Classical Liberal Education and Civic Leadership. Growing up, she was deeply influenced by firsthand accounts of the terrors of communism shared by her grandparents and parents, who risked their lives to escape Romania. These personal narratives, combined with her curiosity about educational systems, motivated her to pursue further research into education during the Romanian communist regime.