Who Were the Victims of the Katyn Massacre?

This article was written by Monika Brzozowska-Pasieka, Ph.D., 2020-2021 VOC Senior Research Fellow in Poland Studies. It is the second in a series of five articles about The Katyn Forest Massacre. To view all five articles, click here.

Many people do not realize that the first genocide of WWII took place in 1940 and is known as the Katyn Forest Massacre. Who were the victims of this crime, committed by the Soviets? The victims were the accomplished Pols –members of Polish intelligentsia and are estimated to have represented 44 different professions.

In its final report, the Madden Committee (an American committee established pursuant to Resolution No. 390 of the American Congress) stated that “there can be no doubt this massacre was a calculated plot to eliminate all Polish leaders who subsequently would have opposed the Soviets’ plan for communizing Poland.”

The victims of the Katyn Forest Massacre were not only Polish soldiers (both professional and in reserve); they were veterans. Nearly all of them had fought in the Polish–Soviet War (the exception being men who were too young to fight, like Staś Ozimek, who was only seventeen when he died, or Józef Marcinkiewicz, a mathematical genius who was ten years old when the Polish–Soviet War broke out).

Many of these victims were called to be soldiers due to the outbreak of war, but before WWII, they were outstanding doctors, lawyers, generals, lecturers and professors, scientists, political leaders, and artists. They were well educated, intelligent, open-minded, prominent, distinguished people, either wealthy before the war or with prospects for great careers. Many had graduated from the best universities in the world, were published in worldwide science journals, worked for foreign universities, medical clinics, or legal practices, and were recipients of foreign scholarships, awards, and prizes.

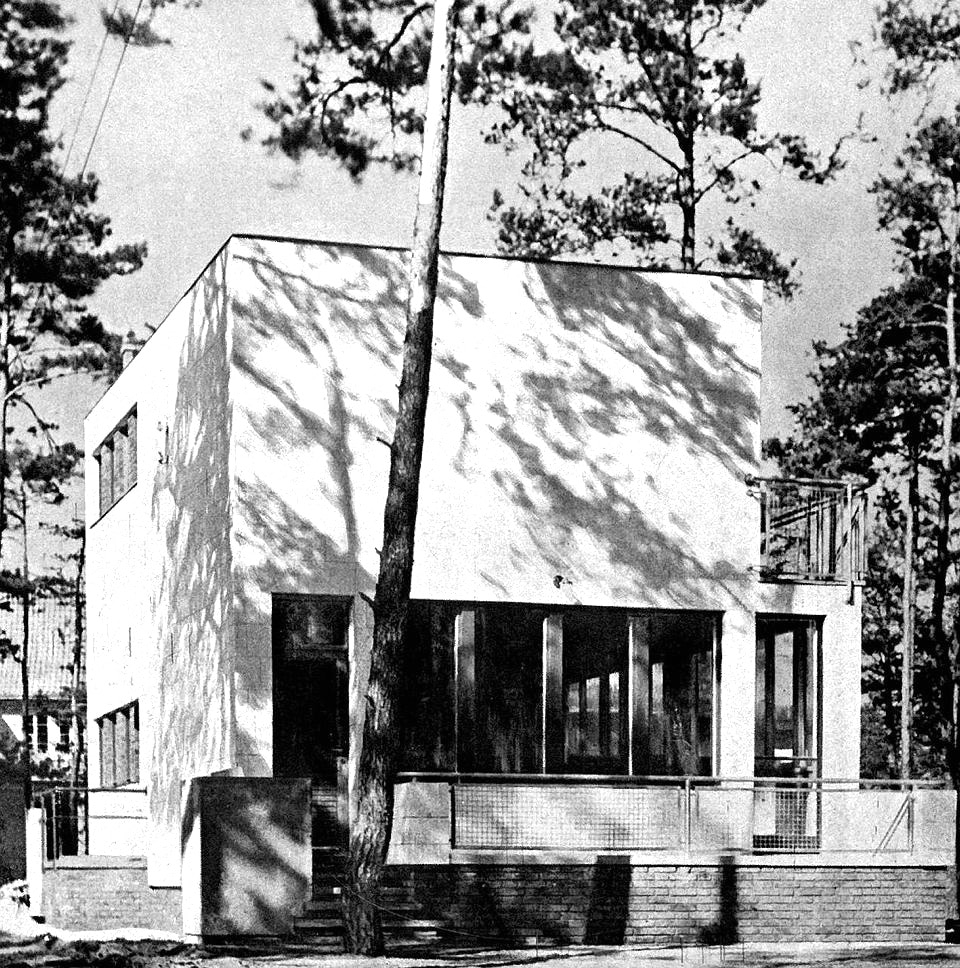

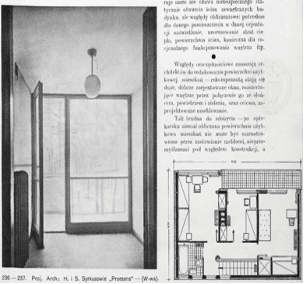

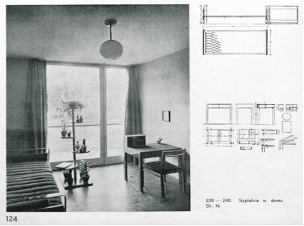

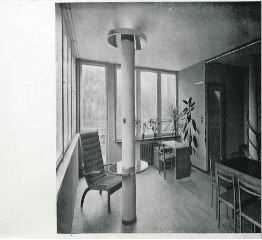

For example, the physician and professor Jan Nelken and his family owned a beautiful house in Konstancin-Jeziorna, Poland, near Warsaw. An outstanding psychiatrist, Nelken could afford to hire two world-famous architects to build the house: Helena and Szymon Syrkus. The house was so avant-garde that the concept and design were described in the professional press in 1935 (Czasopismo Techniczne, issue 10) and photos of the interior (including luxury furniture and modern design items) were published in a design magazine, Wnętrze, in 1933–1934. According to the memoirs of author Małgorzata Kalicińska-Buraczewska, Nelken also owned an apartment on Moniuszko Street in Warsaw, where he lived and had a private practice.[1]

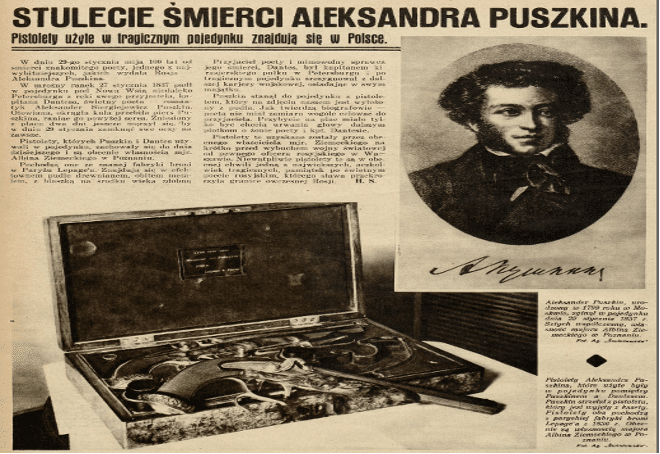

Another victim was the veterinarian surgeon Major Albin Ziemecki, who was an art and weapons collector. His collection was interesting enough to be featured in the pre-war press in 1937, Światowid, as he was the owner of Alexander Pushkin’s revolvers, used in the famous duel in which Alexander Pushkin was killed.

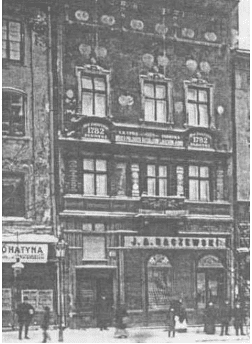

Stefan and Adam Baczewski were co-owners of the well-known company J. A. Baczewski—the biggest producer of alcohol in Poland and one of the biggest in Central Europe. The Baczewski family was one of the wealthiest in the city of Lwow. They owned, among other things, a house in the market square (at number 31) and a factory. They were known as the milionerzy od likierów, or “liqueur millionaires.”[9] Both of the co-owners were murdered pursuant to the Politburo decision of March 5, 1940, in the Katyn Massacre. On behalf of the decision Polish prisoners of war were treated as “enemies of the Soviet authorities filled with hatred for the Soviet system of government” what meant in fact capital punishment for the Poles held in Soviet camps and prisons without bringing any formal charges against them, without investigation and without any trial or indictment.

The Jaxa Bąkowski family – the family of Katyn massacre victim Jerzy Jaxa Bąkowski – owned a manor house and some famous horses. In 1936, some of the horses won many shows in America, where they were transported. The Americans were delighted with their beauty.

Some of the victims’ professions are presented by the following historians:

- Maria Magdalena Blombergowa[14] established that the Katyn, Kharkov, and Mednoye executions had claimed the lives of 6 pharmacists, 8 social scientists, 12 lawyers, 9 veterinarians, 26 scientists (mathematicians, physicists, chemists), 8 representatives of agricultural science, 3 teachers, 27 representatives of art and academia, and 86 physicians.

- Teofan M. Domżał[15] established that among the physicians, there were 18 neurologists and psychiatrists, including 6 professors and docents: Stefan Kazimierz Pieńkowski and Aleksander Ślączka from Cracow; Marcin Zieliński from Poznań; Włodzimierz Godłowski from Wilno; and Stefan Mozołowski and Jan Nelken from Warsaw.

- Andrzej Stonoga and Stanisław Mikke[16] presented at least 111 attorneys at law murdered in Katyn.

- Karolina Wesołowska[17] reported that 21 scientists, professors, docents and university lecturers, several hundred lawyers, several hundred engineers, several hundred teachers, and many journalists, writers, and commentators were murdered at Kozelsk.

- Andrzej Przewoźnik established that among those murdered in the Ukraine (377 Polish civilians, reserve, and inactive officers) there were (among others) 74 landowners, 46 teachers, 70 engineers, 15 physicians, 174 lawyers, 19 district governors and deputy governors, 10 mayors and deputy mayors, the Volhynia governor (Ignacy Strzemiński), 6 senators, 6 members of parliament, and 91 officials.

Additionally, there is evidence that in one camp in Kozelsk, there were two Roman Catholics, one Orthodox priest, one Jewish rabbi, and one Protestant minister who were killed.

Among the victims were 150 athletes, including 10 former Olympians: Józef Baran-Bilewski, Roman Bocheński, Franciszek Brożek, Wojciech Bursa, Zdzisław Dziadulski, Zdzisław Kawecki-Gozdawa, Aleksander Kowalski, reserve Lieutenant Marian Spojda and reserve Lieutenant Stanisław Urban, and in Moscow (pursuant to the decision of March 5), Stanisław Świętochowski.

The number of foresters killed is far from precise. Researchers have provided the following numbers: 100, 120, 190, and even 721 (although the latter is believed to be incorrect). The most appropriate and checked list contains 190 names and was used by Tomasz Skowronek[18]. Wojciech Roszkowski wrote:

According to Soviet documents released after 1990, the number of victims of the 5 March 1940 decision includes 21,857 Polish internees, 4,421 of which came from the Kozelsk camp, 3,820 from the Starobelsk camp, 6,311 from the Ostashkov camp, and 7,305 from prisons in Belorussia and Ukraine. (…) Altogether, during the April and May 1940 massacres, the Soviets murdered almost half of the Polish officer corps, including 14 generals, 281 colonels and lieutenant colonels, and 2,080 majors and captains (….) [T]he Soviets murdered Generals Bronisław Bohatyrewicz, Henryk Minkiewicz and Mieczysław Smorawiński, Admiral Ksawery Czernicki, Chief Orthodox Chaplain of the Polish Army Symon Fedoronko, Chief Rabbi of the Polish Army Baruch Steinberg, and a single woman, Jadwiga Lewandowska, who was daughter to General Józef Dowbór-Muśnicki[19].

These brave and well-educated professionals made up the officer corps. Needless to say, by destroying and murdering the officer reserve corps, the Soviets killed two birds with one stone—not only the military corps, but also the entire educated leadership of a nation.

————————-

[1] Stanisław Ilnicki, “Wspomnienia Pani Małgorzaty Kalicińskiej-Buraczewskiej o rodzinie, przyjaciołach i Szpitalu Ujazdowskim,” Historia Medycyny, accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.mp.pl/lekarzwojskowy/artykul/1760/

[2] Photo from “Żołnierze Niepodległej (III),” Okolice Konstancina, accessed November 15, 2021, https://okolicekonstancina.pl/2018/06/05/zolnierze-niepodleglej-iii/

[3] Photo from Magazin „ Wnętrze” 1933–1934, nr 7 http://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/publication/29487

[4] Photo from Magazin „ Wnętrze” 1933–1934, nr 7 http://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/publication/29487

[5] Photo from Magazin „ Wnętrze” 1933–1934, nr 7 http://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/publication/29487

[6] Photo from Magazin „ Wnętrze” 1933–1934, nr 7 http://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/publication/29487

[7] Photo from from Magazin „ Wnętrze” 1933–1934, nr 7 http://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/publication/29487

[8] Photo from Magazin „Światowid” 1937, nr 5 https://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/Content/229490/PDF/NDIGCZAS001744_1937_005.pdf

[9] See more: Mariusz Grabowski, “Najbogatsi Polacy dwudziestolecia międzywojennego,” Nasza Historia, accessed November 15, 2021, https://naszahistoria.pl/najbogatsi-polacy-dwudziestolecia-miedzywojennego/ar/c3-12227573.

[10] Photo from Sławomir Koper, “Baczewscy – niezwykła lwowska rodzina,” Histmag.org https://histmag.org/Baczewscy-niezwykla-lwowska-rodzina-19304.

[11] The photo of the factory of Baczewskis. Photo from . Sławomir Koper, “Baczewscy – niezwykła lwowska rodzina,” Histmag.org https://histmag.org/Baczewscy-niezwykla-lwowska-rodzina-19304

[12] Photo from „Pisane miłością losy wdów katyńskich” p. 13

[13] Photo from A. Ziółkowska – Bohem „Dwór w Kraśnicy i Hubalowy demon” p. 223

[14] Maria, Magdalena Blombergowa, Uczeni polscy rozstrzelani w Katyniu, Charkowie i Twerze, Analecta 9/2 (18) 7-61, 2000

[15] Teofan M. Domżał, Historia Polskiego Towarzystwa Neurologicznego Klinika Neurologiczna Wojskowego Instytutu Medycznego w Warszawie,ISSN 1734–5251, p. 197

[16] Stanisław Mikke, “Adwokaci – Ofiary Katynia,” Muzeum Historii Polski, 2003, http://bazhum.muzhp.pl/media//files/Palestra/Palestra-r2003-t48-n3_4(543_544)/Palestra-r2003-t48-n3_4(543_544)-s14-17/Palestra-r2003-t48-n3_4(543_544)-s14-17.pdf.

[17] Karolina Wesołowska Sylwetki oficerów lekarzy Wojska Polskiego, jeńców obozu kozielskiego w świetle zapisków grobowych Niepodległość i Pamięć 23/3 (55), 159-180, p. 166

[18] Tomasz Skowronek, Leśnicy i drzewiarze z Pomorza i Kujaw – ofiary zbrodni katyńskiej, Toruń 2013 p. 43 – 58

[19] W. Roszkowski, Communist crimes, p. 174 https://ipn.gov.pl/pl/publikacje/ksiazki/64507,Communist-Crimes-A-Legal-and-Historical-Study.html