The Poznań Protests

How Poland Challenged Communism in 1956

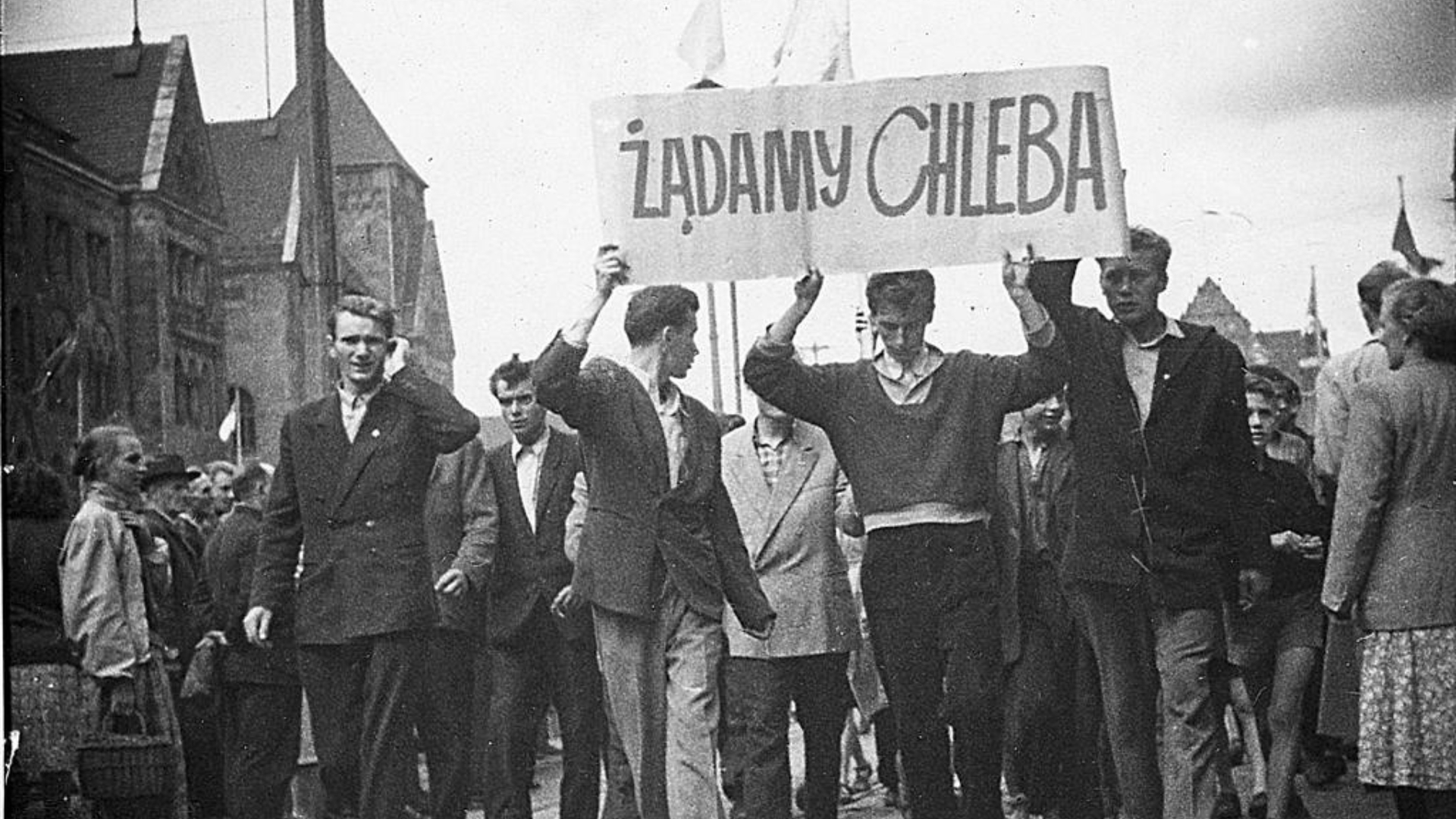

At 6:00 in the morning on June 28, 1956, workers walked out of the Cegielski engineering plant in Poznań, Poland, ignoring the sirens that signaled the start of the day. Under excessive quotas, poor health and safety conditions, low wages, high food prices, and secret police terror, strikers demanded “bread and freedom.” Soon, they were joined in the streets by other factory workers and citizens of Poznań. Eventually, some 100,000 demonstrators gathered in front of the local security ministry building, and what had started as a strike had become something far bigger: an impromptu protest for liberty.

Falling behind Moscow’s Iron Curtain after the Second World War, Poland became an unwilling but key satellite state of the Soviet Union’s Warsaw Pact in the 1950s — the collective defense organization meant to oppose NATO and the West. While “independent” on paper, the Polish People’s Republic was occupied by Moscow’s Red Army, and operated under a Soviet-controlled regime subject to the whims of the Kremlin.

But Stalin’s death in 1953 — as well as the death of the Soviet-appointed Polish leader Bolesław Bierut in February of 1956 — exposed cracks in Moscow’s control. Without Stalin’s reign of terror crushing dissent at home and abroad, Poles were, for the first time, able to acknowledge the reality of life under communism without fear of immediate punishment. And they realized that the terror, oppression, and poor living conditions were not the exception, but the rule.

When strikers abandoned their work that June morning, their grievances ignited the opposition of the Polish people, uniting a nation long held captive by the yoke of communism. As negotiation attempts failed, calls for improved working conditions transformed into cries for freedom. No longer would the people tolerate the regime’s failure to make good on their promise of a “workers’ paradise.”

Poles soon took over government buildings, seized weapons, attacked the local offices of secret police and party functionaries, and destroyed a transmitter jamming radio from the West.

The strike had become an uprising.

The following day, Soviet Marshal and Polish Minister of Defense Konstantin Rokossovsky ordered the military to crush the protests. 58 Poles were killed and well over 200 were wounded, including 13-year-old Romek Strzałkowski.

In the wake of the bloodshed and ensuing unrest, the regime was convinced that changes had to be made to retain the status quo. In response, the regime began to lightly liberalize as Polish authorities increased wages, and promised limited social as well as political reform. Hopes of liberalization were also inspired by the rise of Władysław Gomułka, a Polish politician who had previously been arrested for “nationalist deviation” under Stalin’s reign of terror.

In the “thaw” after Stalin’s death, Gomułka convinced Nikita Kruschev that Poland needed more autonomy from Moscow in order to follow a “Polish road to socialism.” But Moscow’s leniency would be short-lived as reforms soon gave way to yet more oppression.

It would not be until December of 1989 that Poland’s dream of freedom would be realized.

The Poznań protests were a remarkable moment in Poland’s fight against communism. The uprising revealed how far the regime was willing to go to retain power, and showed both sides of the Iron Curtain that cracks were starting to form in Moscow’s rule.

As we remember the Poznań protests and mourn the victims, we must also recognize the message of hope on that day in 1956.

In the end, communism would be defeated by the people it claimed to liberate.