The Lone Female Victim of the Katyn Massacre

This article was written by Monika Brzozowska-Pasieka, Ph.D., 2020-2021 VOC Senior Research Fellow in Poland Studies. It is the fourth in a series of five articles about The Katyn Forest Massacre. To view all five articles, click here.

In 1940 the Red Army, which attacked Poland on September 17, 1939, captured and sent to the camps many Polish soldiers who should have been treated as prisoners of war in the meaning of that term used in international treaties and conventions at that time. Soldiers classified as the most dangerous for the USSR were sent to three “special” camps in Kozelsk, Oshashov, and Starobelsk. The special camps were designated for the most dangerous anti-Soviet “elements”—meaning the Polish patriots’ high-ranking officers.

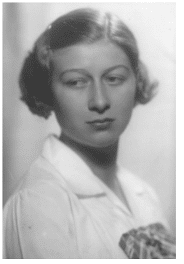

Only men were in the camps, except for one woman who shared the fate of her comrades, ending up in a mass grave and fated to be forgotten like the others. She was the only woman murdered in the Katyn Forest, and her name was Janina Lewandowska.[6]

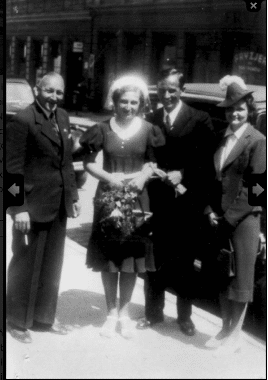

Lewandowska was the daughter of Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki, who was initially a Russian officer and then became a Polish general, and who was well known in Poland, as he had been the military commander of the Greater Poland Uprising (1918–1919).[7]

As a teenager, Lewandowska was an avid pilot, parachutist, and singer. She joined the Poznań Flying Club, where she learned to fly gliders and even to skydive. It was here that she earned her glider and parachuting certificates. After graduating from high school in Poznań, she began studies at the Poznań Music Conservatory to become an opera singer. When she realized that her voice was not good enough, she became serious about gliding and parachuting. When she was twenty-two years old, she became the first woman in Europe to parachute-jump from five thousand meters. On June 10, 1939, she married gliding instructor Mieczysław Lewandowski. They lived fifty-two days as a married couple, but they never lived together. After the breakout of WWII, he was mobilized as a pilot in the Army in Krakow and she lived in Poznań. When the Soviets attacked Poland, she joined the Polish Army. He came back and reached her apartment just a couple hours after she had left. He never met his wife again. During WWII, he was arrested by the Gestapo, sent to a transit camp, and then sent to the General Guberny, from which he escaped to Great Britain. During the war he was a pilot in a Polish squadron. After the war he ended up in Great Britain, where in 1964 he committed suicide.

In 1939, after the outbreak of the war, Lewandowska enlisted as a volunteer in the third Aviation Regiment stationed in Poznań-Ławica. Although women were not allowed to serve in the Polish Army, she was permitted to join; one cannot forget she was an excellent pilot and a daughter of a famous Polish general.

Lewandowska was captured by the Soviets and detained at Kozelsk. Why she ended up in the Katyn camp is still unclear. Some historians believe that she had borrowed an officer’s uniform; others believe that she was being investigated by the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD)—the Soviet secret police—as the daughter of a man whom the Russians hated (General Józef Dowbór-Muśnicki),[8] and that her stay in the camp was not accidental. She was likely killed on her thirty-second birthday.

The Germans, who discovered the Polish soldiers’ graves in Katyn in 1943 and who spread the information about the massacre all over the world, were confused when they found a female body in the Katyn graves. They decided not to disclose this information (it did not fit in with the male bodies of the Polish officers and could destroy the message they wanted to spread). They did not put Lewandowska’s name on the list. Consequently, her family was not aware that she had perished at Katyn.[9]

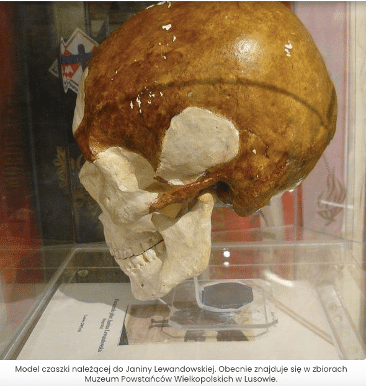

In 1943, German professor Gerhard Buhtz, who headed the exhumation of the Polish soldiers, took away with him seven skulls, including that of Lewandowska. In 1945, the skulls ended up in the hands of University of Wrocław professor Bolesław Popielski (a Polish forensic medicine specialist), who hid them from the Security Policy and the NKVD. In 1997, just before he passed away, he informed his colleagues about this mystery, but research on the skulls commenced only in 2003. One of the skulls was thought to be female, but this was impossible to prove via DNA testing. Therefore, in order to identify the owner, a new forensic method called superprojection was used. Lewandowska’s photo was projected onto the skull, which allowed the scientists to confirm her identity. In 2005, the skull was buried in the cemetery in Lusowo in the Dowbor-Muśnicki family vault.

It should be noted here that Lewandowska’s sister and General Dowbor-Muśnicki’s second daughter, Agnieszka Dowbor-Muśnicka, was killed by the Germans at Palmiry in 1940. The execution took place near Warsaw, where the Germans killed 1,700 people, including members of the Polish intelligentsia. Nazi Germans used the same rationale for killing the Polish elite as the Soviets did. The fate of the two killed sisters is often presented as a fate of Poland—attacked and devastated by two powers: the German one and the Russian one.

The photo below is a “silent witness” of the tragic fate of Polish citizens under German occupation. It presents Polish women being led by the Germans to their place of execution. It’s likely that a German soldier who participated in the execution took the photo.

Returning to Janina Lewandowska—she was the only woman detained in the special camp and murdered in the Katyn forest.

However, some fifty-four women were executed pursuant to the decision of March 5, 1940, issued by the Soviet Politburo.[13] These women were arrested after the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939. Most of them were the wives of Polish soldiers detained in Soviet camps. The youngest woman murdered was Aniela Krotochwilówna—an eighteen-year-old arrested as an agent of the Polish police. The oldest women were Helena Lewczanowska and Nadieżda Stiepanowa, both born in 1881 (fifty-nine years old at the time of death).[14]

It is worth noting that there were at least sixty-five children in the camps[15]—teenagers and boys, the youngest of whom was six years old. They should have been treated as prisoners of war. Only some of them survived; the fate of some remains unknown, and a handful were killed alongside their fathers (including Stanisław Ozimek, a seventeen-year-old scout at the time of his death in 1940, just two months before his eighteenth birthday). [16]

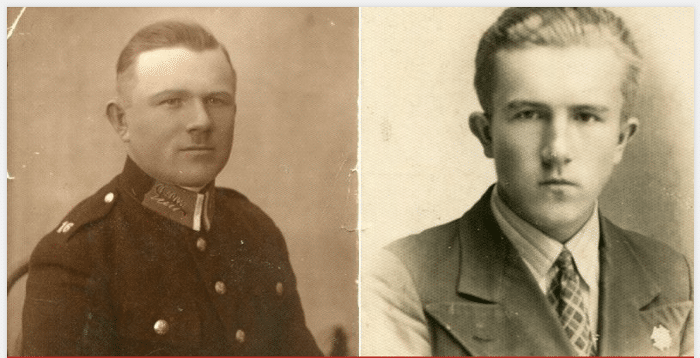

Stanisław and his father, Jan Ozimek, are shown in the photos below. On October 19, 1939, Red Army soldiers made a decision that nine young boys detained with their fathers (policemen) could return home, but Stanisław decided to stay with his father. Jan Ozimek died on April 16, and his son was murdered between May 5–19, two months before his eighteenth birthday. They were the only father-and-son pair killed in the Katyn Massacre.[17]

Another boy known by name and killed in 1940 was Adam Tabaczyński, who in 1939 was seventeen years old[18] and was a cadet in Lwow. He was killed at Katyn.

One of the executions of boys is described by Tokarev Dmitrii, who was the head of the NKVD branch in the Kalinin/Tver region in 1940:

I didn’t cross-examine anyone except a boy, whom I asked, “How old are you?” He said “eighteen.” “Where did you serve?” “In the border guard.” What did you do?” He was a telephone operator. (…) I believe he was without a hat. He entered and smiled like a boy, a complete boy, eighteen years old, and how long had he worked? He began counting in Polish—“Six months.”[19]

The children were the sons of Polish State Police officers and soldiers of the Polish Army. Being scouts or cadets, they had fought against the Soviets with their fathers. Some of the children were released, although the fate of many remains unknown.[20]

Historians point out that there was a six-year-old boy in Starobelsk, named Andrzej Jagodziński, born in 1933, the son of Captain Czesław Jagodziński, and perhaps the youngest prisoner. He was deported from the Katyn camp on May 8, 1940, most probably to Kharkov. He survived, returned to Poland, gained a higher-education degree and worked at the Passenger Automobile Factory in Warsaw as a master engineer. He died in 1960, likely shot by the Security Service[21] because, some sources say, he was suspected of speaking out about his stay at Katyn.

The Katyn Massacre included not only men of the Polish military service but also children, women, and families of the Katyn Massacre victims. One cannot forget that the Katyn families, after the Katyn Massacre, were persecuted, deported deeply into Russia, or killed by unknown perpetrators. One cannot forget these Russian crimes.

———————————–

[1] Photo from “Janina Lewandowska,” Wielkopolski Urząd Wojewódzki w Poznaniu, accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.poznan.uw.gov.pl/panteon-wielkopolanki/janina-lewandowska

[2] Photo from “Janina Lewandowska,” Historia Poszukaj, accessed November 15, 2021,https://www.historiaposzukaj.pl/wiedza,osoby,822,osoba_janina_lewandowska.html.

[3] Photo from “Janina Lewandowska – The Only Servicewoman Murdered in Katyn,” Institute of National Remembrance, March 4, 2020, https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/4029,Janina-Lewandowska-the-only-servicewoman-murdered-in-Katyn.html.

[4] Photo from “Janina Lewandowska,” Wielkopolski Urząd Wojewódzki w Poznaniu, accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.poznan.uw.gov.pl/panteon-wielkopolanki/janina-lewandowska

[5] Photo from “Janina Lewandowska,” Wielkopolski Urząd Wojewódzki w Poznaniu, accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.poznan.uw.gov.pl/panteon-wielkopolanki/janina-lewandowska

[6] “Janina Lewandowska – The Only Servicewoman.” For more, see: Łukasz Zalesiński, “Metal Plane,” Polska Zbrojna, April 2020, https://zbrojni.blob.core.windows.net/pzdata2/TinyMceFiles/jednodniowka_katyn_04_2020_ang.pdf

[7] See more: “Greater Poland uprising (1918–1919),” Wikipedia, last modified September 22, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greater_Poland_uprising_(1918%E2%80%931919)

[8] See more: “Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki,” Wikipedia, last modified August 3, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C3%B3zef_Dowbor-Mu%C5%9Bnicki

[9] See more: “Janina Lewandowska. Kim była jedyna kobieta, która zginęła w Katyniu?,” ciekawostki historyczne.pl, May 2, 2018, https://ciekawostkihistoryczne.pl/2018/02/05/kim-byla-jedyna-kobieta-ktora-zginela-w-katyniu/.

[10] Photo from “Janina Lewandowska. Kim była jedyna kobieta, która zginęła w Katyniu?” ciekawostki historyczne.pl.

[11] Photo from “Córki Generała: Janina Lewandowska,” Museum of Greater Poland Uprising, accessed November 15, 2021, https://muzeumlusowo.pl/corki-generala

[12] Photo from https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zbrodnia_w_Palmirach

[13] Because of the March 5 decision, Polish prisoners of war were considered “enemies of the Soviet authorities filled with hatred for the Soviet system of government.” This led to capital punishment for the Poles held in Soviet camps and prisons, without any investigation, trial, indictment, or formal charges against them.

[14] See more: “Ofiary,” Katyn 1940, accessed November 15, 2021, https://katyn.ipn.gov.pl/kat/ludzie/ofiary/12144,Ich-juz-nie-ma.html

[15] Maryla Fałdowska, “Children of State Police Officers and Soldiers of the Polish Army in NKVD Special Camps,” Internal Security, July–December, accessed November 15, 2021, DOI: 10.5604/01.3001.0013.4227

[16] “A father and son, victims of the Katyn Massacre and protagonists of the IPN’s latest exhibition,” Institute of National Remembrance, September 16, 2020, https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/4590,A-father-and-son-victims-of-the-Katyn-Massacre-and-protagonists-of-the-IPN039s-l.html?sid=b7a6023b325af6d50d17913c06448920

[17] “A father and son,” Institute.

[18] For more information, see: “Kadet Adam Tabaczyński,” Katyn 1940, accessed November 15, 2021, https://katyn.ipn.gov.pl/kat/ludzie/ofiary/baza-wyszukiwarka/r69432705,TABACZYNSKI.html

[19] “Zeznanie Tokariewa,” Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, accessed November 15, 2021, https://edukacja.ipn.gov.pl/edu/materialy-edukacyjne/wirtualna-paczka-edukac/zbrodnia-katynska/materialy-do-pobrania-i/92589,Zeszyty-Katynskie.html

[20] See more: Ewa Kowalska, “Małoletni więźniowie obozów specjalnych NKWD (1939–1940),” Dzieje Najnowsze, 2019, https://apcz.umk.pl/czasopisma/index.php/DN/article/download/DN.2019.2.16/18119.

[21] See more: “Transport zamiast na miejsce przeznaczenia dotarł do Lwowa. Był w nim najmłodszy jeniec – 7-letni Andrzej Jagodziński,” wnet.fm, November 20, 2017, https://wnet.fm/kurier/transport-zamiast-miejsce-przeznaczenia-dotarl-lwowa-byl-nim-najmlodszy-jeniec-7-letni-andrzej-jagodzinski/.