Chapter 7

Famine as a Weapon

“Here I saw people dying in solitude by slow degrees, dying hideously, without the excuse of sacrifice for a cause. They had been trapped and left to starve, each in his home, by a political decision made in a far-off capital around conference and banquet tables. […] The most terrifying sights were the little children with skeleton limbs dangling from balloon-like abdomens. Starvation had wiped every trace of youth from their faces, turning them into tortured gargoyles; only in their eyes still lingered the reminder of childhood. Everywhere we found men and women lying prone, their faces and bellies bloated, their eyes utterly expressionless. Anger lashed my mind as I drove back to the village. Butter being sent abroad in the midst of the famine! In London, Berlin, Paris I could see with my mind’s eye people eating butter stamped with a Soviet trademark. ‘They must be rich to be able to send out butter,’ I could hear them saying. ‘Here, friends, is the proof of socialism in action.’ Driving through the fields, I did not hear the lovely Ukrainian songs so dear to my heart. These people had forgotten how to sing. I could hear only the groans of the dying, and the lip-smacking of fat foreigners enjoying our butter.”

Ukrainian-born, dedicated Communist Party member Victor Kravchenko was mobilized by the Soviets to organize and safeguard the Ukrainian harvest of 1933. He rose to the rank of Red Army captain during World War II, was posted to Washington, D.C., and defected in 1944. His 1946 memoir is a modern classic.1

The Famine’s Beginning: The Five-Year Plan

Through the late 1920s and early 1930s, Joseph Stalin continued to pursue Vladimir Lenin’s totalitarian vision of communism. All aspects of society, especially economic production, were to be brought under state control.2 Stalin laid out his economic design for the Soviet Union in his first Five-Year Plan, in which the rapid industrialization of urban areas was to be supported by the near complete collectivization of agriculture in rural communities.3 The workers would be fed by confiscated grain and food, while machinery and foreign debt would be financed by cash from agricultural exports. How the peasants would survive did not trouble the plan’s architect.

Stalin was determined to make the Soviet Union an industrial powerhouse to rival the West, and he saw collective farms as the key. Stalin ordered a country-wide effort to turn private farms into state-run agricultural collectives, which he believed would be more productive than either capitalist or traditional peasant methods. The quotas were unreasonably high, however, based as they were on what the state wanted, rather than what the peasants could actually produce. The Soviet government forcibly confiscated most of the farmers’ harvests, and often imprisoned or executed those who failed to meet their unrealistic requirements.4 Despite warning signs of failure in agriculture, communist ideology prevented the Soviets from accepting that the plan was failing.5 Indeed, Stalin claimed that harvests were better than ever, and that the shortage must be due to counter-revolutionaries infiltrating the collectives.6 He urged officials to implement the plan more aggressively, regardless of the rising human cost. When the starving peasants openly protested the regime’s disastrous agricultural policies and the confiscation of even their seed crops, Stalin and the Communist Party once again found in the kulaks a convenient scapegoat.7

To Stalin and the Communist Party, the kulaks—that is, peasants who had been relatively successful under the old system–presented a threat to collectivization. To be sure, the kulaks had been demonized and persecuted since Lenin’s time. Nonetheless, Stalin urged officials not to be complacent: “The present-day kulaks and kulak agents, the present-day anti-Soviet elements in the countryside are in the main ‘quiet,’ ‘smooth-spoken,’ almost ‘saintly’ people. There is no need to look for them far from the collective farms; they are inside the collective farms.”8 He did not mince words: “In order to oust the kulaks as a class, the resistance of this class must be smashed in open battle and it must be deprived of the productive sources of its existence and development.”9 To distract from the utter failure of his agricultural policies, Stalin, like Lenin before him, identified the kulaks as saboteurs and enemies of the Soviet Union, communism, and the Soviet people.10

A Soviet grain cart transports crops from a collective farm in Kharkiv. Photo via the

Central State Audiovisual Archives of Ukraine.

Ukraine Becomes the Target: The Holodomor

Over the course of the next three years, Stalin’s anti-kulak policy and forced collectivization became increasingly brutal. Desperate peasants flooded to the cities in search of food and jobs, draining the country of rural labor and creating untenable overcrowding in the cities. Alarmed, the Kremlin issued a top-secret memo mandating that kulaks remain in the countryside, and in December 1932 initiated a system of internal passports.11 Without papers, city residents were subject to immediate arrest and deportation.12 Kulaks, of course, were denied passports, effectively making it impossible for them to leave their homes. By the end of 1932, the Soviets’ economic plan had inflicted serious, far-reaching harm on agriculture production. The new system proved unworkable, and the poor agricultural output created a crisis across all the Soviet Union.

Nowhere was this man-made famine more catastrophic than in Ukraine. Known as the Holodomor (a combination of the Ukrainian words holod, “hunger” and moryty, “to kill by privations, to exhaust”), the engineered famine killed approximately 4 million people.13 “People began to die in 1932. And it wasn’t because the harvest was bad. That year there was a gorgeous harvest. The Famine was the result of the confiscation of everything the peasants had,” said one survivor of the Holodomor.14 Keeping, saving, or hiding any food brought severe punishment. A Soviet law enacted in August 1932–the Law of Five Ears of Grain–stated that anyone, even a child, caught taking any produce from a collective field could be shot or imprisoned for stealing socialist property. A decree in January 1933 sealed the borders. Those caught attempting to flee to the cities or beyond Ukraine’s borders, where conditions were better, were imprisoned or sent home to die.15 Historians estimate that by 1933, Ukrainians were dying at a rate of 28,000 per day.16 Despairing Ukrainians resorted to extreme measures. As the famine intensified, the struggle became moral as well as physical:

“The good people died first. Those who refused to steal or to prostitute themselves died. Those who gave food to others died. Those who refused to eat corpses died. Those who refused to kill their fellow man died. Parents who resisted cannibalism died before their children did. Ukraine in 1933 was full of orphans, and sometimes people took them in. Yet without food there was little that even the kindest of strangers could do for such children. The boys and girls lay about on sheets and blankets, eating their own excrement, waiting for death.”17

Stalin and the Politburo were fully aware of the catastrophe taking place in Ukraine because they themselves had ordered it. Officially, however, the regime denied that the famine was occurring. Even discussing the famine in public carried a five-year Gulag sentence, and blaming the disaster on government authorities was punishable by death.18 Sadly, Ukraine was not the only Soviet republic to suffer under forced collectivization. In Kazakhstan, for example, the brutal enforcement of collectivization and rapid societal change (such as forcing traditional nomads into cities) resulted in the deaths of 1.5 million people.19 Ukraine, however, as the agricultural center of Russia—and the breadbasket of Europe–suffered the most.

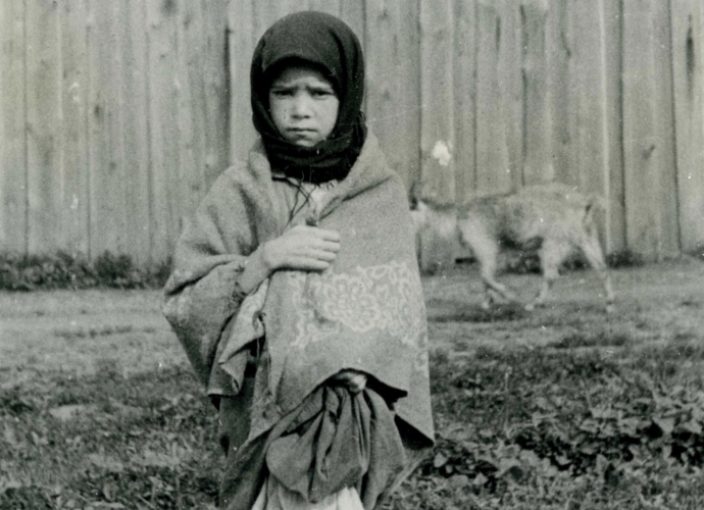

A starving girl in Kharkiv during the Holodomor. Photo by Alexander Wienerberger.

Stalin and Western Media Hide the Famine and Death Toll

The Soviet leadership, aware of the atrocity, continued to impose their policies. Furthermore, they covered up all news of the famine and hid the realities of their repressive measures and the Holodomor’s death toll—both from their own citizens, and from the world.20 Disinformation and propaganda played a major role in the Kremlin’s concealment of the genocide, with the complicity of Western journalists. Forbidden to travel without official minders, and fearful of risking ejection or worse, the press corps in Moscow was content to simply pass on what the Kremlin told them. Moreover, special perks were available for journalists, such as Walter Duranty of the New York Times, who willingly toed the line.21 In March 1933, Duranty reported that “[t]hese conditions are bad, but there is no famine” and “to put it brutally—you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.”22 Later that year, Duranty wrote that “any report of a famine in Russia is today an exaggeration or malignant propaganda.”23 For his “reporting,” Duranty received wealth, fame, and a Pulitzer Prize. Historians debate whether Duranty was fraudulent or merely credulous—the Pulitzer Committee has declined to withdraw his prize—but it is worth noting that according to U.S. diplomat A.W. Klieforth, “Duranty pointed out that ‘in agreement with the New York Times and the Soviet authorities,’ his official despatches [sic] always reflect the official opinion of the Soviet regime and not his own.”24

Joseph Stalin in Moscow accompanied by Soviet security. Photo via the public domain.

Duranty was the most famous famine-denier, but other correspondents were complicit as well. Louis Fischer, a devoted communist and Soviet apologist, wrote in The Nation, “I think there is no starvation anywhere in Ukraine now — after all they have just gathered in the harvest, but it was a bad harvest.”25 Indeed, the entire Western press corps was aware of the horror engulfing Ukraine, and turned a blind eye. As Eugene Lyons of the United Press later admitted, “Inside Russia the matter was not disputed. The famine was accepted as a matter of course in our casual conversation at the hotels and in our homes.”26 Even when reports leaked out, newspapers suppressed them: The Manchester Guardian heavily edited and excised the eye-witness reports that Malcom Muggeridge smuggled out of the country.27 When Welsh journalist Gareth Jones reported his own eye-witness accounts, he was denounced and discredited by those same journalists who knew the truth, but parroted the official line.28 Duranty himself openly mocked Jones in the New York Times.29

In 1937, four years after the worst of the Holodomor had subsided, the Kremlin conducted its first census in 11 years. Having failed to grasp the scale of their own atrocities, the Soviet leadership quickly realized the results of the census did not align with their vision of population growth and human development. Dismayed, Stalin moved to suppress the census results, arresting and executing the census takers to prevent the realities of the Holodomor from leaking to the public.30 The Soviet Union refused to acknowledge the existence of a famine until the 1980s.31