Chapter 6

Joseph Stalin

and the Soviet Union

“They began to beat me – a sick, sixty-five-year-old man. They made me lie face-down and beat the soles of my feet and my spine with a braided rubber whip. Then they sat me on a chair and beat my legs from above with great force. In the days that followed, when those parts of my legs were covered with extensive internal hemorrhaging, they beat the red, blue, and yellow bruises with the whip. The pain was so intense it felt like boiling water was being poured on these sensitive areas. I shouted and cried from the pain.”

Famed Soviet theater director, actor, and producer Vsevolod Meyerhold answered a knock on the door in the early morning of June 20, 1939. He was arrested and tortured, his wife was murdered, and he was executed by firing squad on February 2, 1940.1

Introduction: Stalinism

After Vladimir Lenin’s death in 1924, Joseph Stalin took control and intensified the totalitarian rule of the Soviet Union until his own death in 1953. His leadership significantly shaped the course of world history, particularly within the context of World War II and the Cold War. Stalin’s political career was a complex and often contradictory mix of policies and actions, from his industrialization and collectivization campaigns to the purges and systematic repression that marked his reign. Defined by brutality, Stalin’s ideology represented both continuity and departure from Leninism.2

Stalin’s rivals often portrayed him as a plodding bureaucrat distinguished only by his crude hunger for power. Leon Trotsky, a key Lenin ally and Soviet trailblazer, thought Stalin lacked revolutionary fervor: “Unable to catch fire himself, he was incapable of inflaming others. Cold spite is not enough for mastering the soul of the masses.” And further, “The absence of his own thought, of original form, of vivid imagery—these mark every line of his with the brand of banality.”3 As if to underscore this characterization, Stalin exiled his rival from the USSR in the late 1920s, judged and found him guilty in absentia during the Moscow show trials in the 1930s, and ordered his assassination. The last attempt on Trotsky, then living in Mexico, succeeded in 1940.

Many scholars have adopted this portrait of Stalin as a coarse, boorish schemer, a mediocre opportunist utterly consumed by his own ambition. The reality is more complicated. Stalin did not finish his formal education, but he read voraciously on a wide range of subjects, eventually amassing a library of around 25,000 books, most of them heavily annotated.4 As historian Ronald Grigor Suny puts it, “His intellectual interests, however, were directed toward confirmation rather than questioning. . . . His own lack of conceptual facility actually aided him in presenting a reduced message plainly to plain folk, and he gained a following that appreciated this quality.”5 Where Lenin’s mind was agile, Stalin’s was dogmatic; what he lacked in sophistication, Stalin made up for in excess.

This is not to say that Stalin had no ideology of his own. Indeed, communism under Stalin extended and diverged from Leninism in several notable ways. Fixated on rapid industrialization, Stalin forcibly, violently, wrenched a largely agricultural society into the modern world with a series of Five-Year Plans designed to take full, centralized control of the national economy. The Soviet Union emerged as a world power during Stalin’s “revolution from above” —but at a tremendous human cost. Millions died.6 Those who lived still suffered in many ways. Under Stalinism, all aspects of culture, both public and private, were restricted by an oppressive bureaucracy, overseen by the obsessive eye of the dictator himself. Control of the media and censorship of expression were absolute. Artists became propagandists, required to create ideological content in art under the trend of realism. Intensive government surveillance and persecution of suspected saboteurs were carried out by the expanded secret police, the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs. Anyone questioning the state could find himself deported in the dark of night to a labor camp. The totalitarian fist of Stalinism repressed all dissent with violence, imprisonment, and psychological terror.

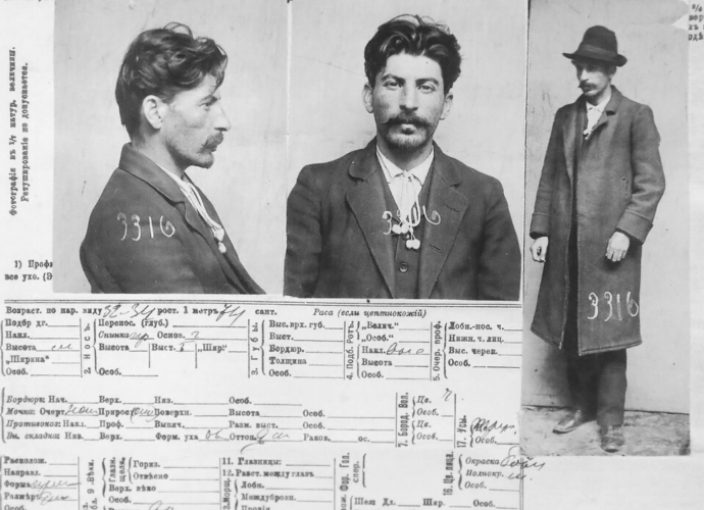

Police mugshots and files of Stalin in 1911. Photo via the public domain.

Stalin’s Early Life

Joseph Stalin (1878-1953) was born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili in the small Georgian town of Gori, about 50 miles outside the capital, Tiflis (later renamed Tbilisi). His father was an alcoholic cobbler who beat his wife and son; his mother was a devout washerwoman.7 Joseph was their only living child. His mother, Ekaterine, left her husband when Joseph was still small, taking in laundry and dressmaking jobs to make ends meet. Through the perseverance of his mother and the connections of a family friend, Stalin attended school—the first in his family to do so.8 He was an excellent student, who wrote poetry and sang in the church choir.9 His father was opposed to his son’s schooling, at one point even kidnapping him and forcing him to serve a short, unhappy apprenticeship in a shoe factory before he was rescued by local priests. This would be Stalin’s only experience with manual labor.10

Stalin then attended the prestigious Tiflis Spiritual Seminary, where he studied theology, Latin, Greek, mathematics, history, and literature. It was there that he openly declared his atheism.11 Under Imperial Russian rule, the seminary attempted to stamp out Georgian culture and language to promote loyalty to the Tsar. Although Stalin would later pursue his own violent policy of Russification, at the time he associated with more rebellious students, wrote pro-Georgian poetry, and sought out banned books, including Marx’s Capital.12 Marxist thought at the time was not considered a serious threat to the Russian Empire, but Stalin increasingly became attracted to revolutionary thinking and studied and admired Lenin.13 Through the early 1900s, after leaving the seminary (he would later claim that he was expelled for revolutionary activity),14 Stalin edited Marxist newspapers and organized demonstrations—not to mention the robberies, extortions, and kidnappings with which the revolutionary groups funded their activities.15 He was arrested by the Tsarist police and sent into exile multiple times. And he caught the eye of leading Bolsheviks, including Lenin. In 1912 he was asked to edit the Bolshevik newspaper Zvezda (The Star), which he renamed Pravda (The Truth). In 1913, Lenin requested that Stalin write about the issue of nations and nationalism within the international communist movement.16 It was at this time that he adopted the pseudonym Stalin (from the Russian word for steel, or roughly “Man of Steel”), which he would keep for the rest of his life.

Although a minor player in the October Revolution, Stalin had already proved his allegiance and quickly rose in the ranks. He was ruthlessly committed to the cause and perfectly willing to use violence and state terror against all political enemies of the Bolsheviks.17 During the Red Terror, the Russian Civil War, and the Polish-Soviet War, Lenin came to depend on Stalin’s loyalty and ferocious organizational talents.18 Political rivalries were rife within the Communist Party, and in the early 1920s Lenin rewarded his dedicated ally with a new position in the Soviet Politburo: General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party.19 Stalin would ultimately find it an ideal perch from which to seize control.

Stalin wearing an Order of the Red Banner in 1921. Photo via the public domain.

Stalin’s Transition to Power

As General Secretary, Stalin worked quietly and strategically behind the scenes to involve himself in all the administrative workings of the Party. He appointed allies, squeezed out rivals, and, most crucially, gathered information.20 By the time Lenin recognized the downside to Stalin’s management acumen, it was too late. In failing health, Lenin dictated a “testament” in two parts (December 1922 and January 1923), in which he criticized all his likely successors and observed, “Comrade Stalin, having become Secretary-General, has unlimited authority concentrated in his hands, and I am not sure whether he will always be capable of using that authority with sufficient caution.”21 Stalin, meanwhile, was taking all precautions to set himself up as Lenin’s successor.22 Following Lenin’s death in 1924, Stalin faced opposition from others in the Politburo.23 In a series of shifting alliances, he arranged the isolation and removal of key political opponents and even their erasure from Soviet history books—most notably Trotsky, who famously referred to Stalin as, “The Gravedigger of the Revolution.”24 By 1929, Stalin was the Communist Party’s supreme leader, the undisputed head of a communist state that even Trotsky had called totalitarian.25

Communism relies on state planning, which Stalin took to new heights. In 1928-29, he implemented his first Five-Year Plan. Alarmed that the USSR was so far behind Western Europe in industrialization, the Communist Party determined to take extreme measures. Grain was required to feed factory workers in the cities, but the peasants, still reeling from the havoc of the civil war, were falling behind in their state-imposed quotas.26 In 1928, Stalin sent grain procurement squads to Novosibirsk, Western Siberia, and the Urals, resulting in violent clashes between the squads and the peasantry.27 Claiming that grain was being hoarded by the kulaks–so-called “wealthy” peasants–Stalin initiated his policy of “dekulakization,” (1929-30) aiming “to smash and eliminate the kulaks as a class.”28 In fact, the term “kulak” was highly elastic. Wealth among the peasantry was relative and could simply mean anyone who hired part-time help or owned more than two cows.29 Soon the term became a convenient excuse to attack or despoil political (or perhaps personal) enemies.30 Accused kulaks were “re-educated,” exiled, and expelled from their homes, their grain and all their property seized and sent back to Moscow. After 1929, many were sent to the expanding system of labor camps known as the Gulag, where they were forced to build infrastructure for the new industry on the frozen steppes of Siberia.31 Many thousands of men, women, and children died during the journey and in the camps of exhaustion, disease, and privation.32 By 1931, 380,000 households—approximately 1,800,000 individuals—were “relocated,” as Stalin’s first mass terror plan was implemented.33

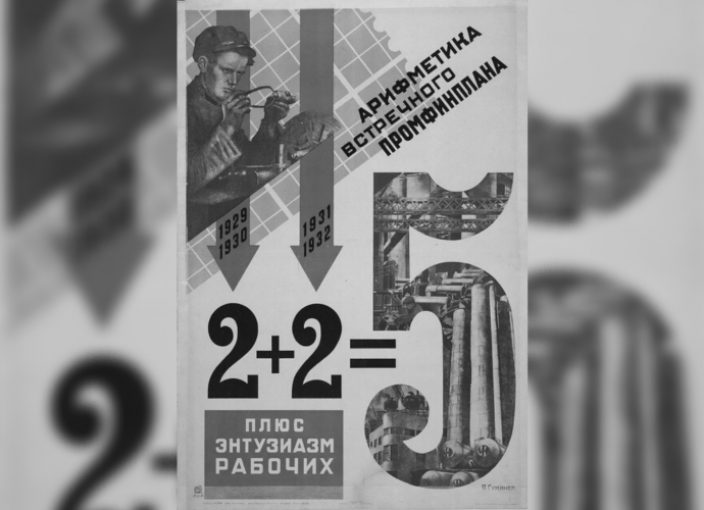

A Five-Year Plan propaganda poster by Yakov Guminer. Photo via the public domain.

Stalin also made communism’s abolition of private property especially painful for millions of peasants across the Soviet Union with his collectivization program.34 In 1929, there were 25 million peasant households, only 1 million of which had been collectivized.35 Impatient to realize their vision, the Politburo approved the forced collectivization of agriculture, requiring the seizure and transfer of farmland owned by individuals to collective, state-controlled farms.36 The Communists forced peasants to join these farms with violence and intimidation, and many more joined out of fear of being labeled a kulak.37 By 1932, roughly 62 percent of Soviet farms were collectivized; by 1936, it was 90 percent. With so much of the nation’s food stores being confiscated and sent to Moscow, residents of agricultural regions were left with little to no grain.38 Social disruption and resentment, not to mention the elimination of the most knowledgeable and productive farmers, caused a drop in productivity, as collective farms had no incentive to produce more than their quotas–which in any case were totally unrealistic.39 In protest, many peasants slaughtered their livestock, destroyed or sold their equipment, and refused to work.40 The result was widespread famine, with its attendant evils of death, disease, homelessness, and child abandonment.41 Although much of the country was angry and starving, Stalin proclaimed that the Soviet Union was “Dizzy with success.”42

Above all, Stalin’s Five-Year Plan was meant to prove communism’s superiority over the capitalist West through the rapid industrialization of the Soviet Union.43 Stalin emphasized heavy industry and set a goal of a 250 percent increase in overall industrial development and a 330 percent expansion in heavy industry.44 To achieve this unrealistic target, Stalin moved resources, manpower, and funding into industrial production.45 Laborers working in factories were given the most food, leaving the rural areas to starve.46 Whatever was left over after the Red Army and Communist Party officials took their share was sold abroad.47 Peasants were forced into Stalin’s industrialization programs, which only worsened food production troubles as lifelong farmers were taken from their farms and forced to work in factories.48 While Stalin’s programs caused famine across the USSR, the worst occurred in Ukraine, where 3.6 to 6 million citizens starved to death.49 Ukrainians who attempted to leave or hide grain from Soviet authorities were executed or sent to the Gulag.50 Throughout, Stalin refused to acknowledge that his policies contributed to the famine. Indeed, he brushed off the colossal human cost of industrialization, saying, “When the head is off, one does not mourn for the hair.”51 He even managed to hide the famine from the outside world, with the help of credulous and sympathetic American journalists from the New York Times and The Nation.52

Stalin (second to top right) overseeing a military parade in Moscow. Photo via the public domain.

Stalin’s Reign of Terror

Stalin was not without his critics, and the brutality of his Five-Year Plan gave some Party members pause.53 As criticism increased, so did Stalin’s paranoia. He moved to solidify his control over the Communist Party and the USSR through two successive purges known as the “Great Purge” and the “Great Terror” (1936-1938). Everyone was at risk — political apparatchiks, military officials, and even Stalin’s inner circle—as he was willing to eliminate anyone who could pose a threat to his power.54 “Death solves all problems,” he used to say. “No man—no problem.”55 He became obsessed with foreign spies and designated entire ethnic groups for elimination for supposed “espionage, terrorism, and other anti-Soviet activities.”56 In 1936, Stalin initiated the bloody “Polish Operation,” in which over 144,000 ethnic Poles were arrested, and the vast majority shot.57 “Very good!” he wrote. “Kick and exterminate the Polish spy-filth.”58 Nor were Poles the only targets: mass terror against ethnic Germans, Romanians, and other groups was official Soviet policy. Orthodox priests were targeted as well, with 136,900 arrested in 1936 alone.59 Actual guilt wasn’t important; membership in a disfavored class was enough.

For political rivals, Stalin was not satisfied with arrest and execution. Elaborate show trials were carefully staged to humiliate critics and neutralize their influence.60 Private citizens were subject to 15-minute trials, with confessions obtained through extreme torture.62 To curry favor, informants would provide information or manufacture evidence where none existed. During this period and long thereafter, individuals were terrified to speak against Stalin for fear of death or being sent to the Gulag, where prisoners eked out a miserable existence, were worked to death, or simply died of hunger or disease.63 While imprisoned, Vsevolod Meyerhold, the legendary Soviet theater director, described his experience: “I began to incriminate myself in the hope that this, at least, would lead quickly to the scaffold.”64 Under Stalin, at least 14 million citizens (about twice the population of Arizona) were sent to the Gulag system across the Soviet Union, with 1.6 million or more dying due to exhaustion, exposure, starvation, disease, or execution.65 By 1938, Stalin had eliminated all threats and opposition to his reign — real and imagined.

Soviet and Nazi soldiers meet after invading Poland in 1939. Photo via the German Federal

Archives under CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Stalin’s Pact with Hitler Begins World War II

In August 1939, Stalin and Adolf Hitler–both totalitarian rulers with imperialist ambitions in Europe—shocked the world by signing the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Ostensibly a non-aggression treaty, the Pact included a secret plan to carve up large portions of central and eastern Europe, dividing it between the Communists and the Nazis. Hitler invaded Poland one week later, on September 1, 1939, and Stalin shortly thereafter. The Second World War had begun. By June 1940, the Soviet Union had occupied the Baltic States and invaded parts of Romania. Stalin also exported communism’s tools of violence, particularly in Poland. In the course of the war, over one million Poles were arrested and tortured or deported to Siberia, unless they were summarily executed. Stalin personally ordered the execution of 22,000 Polish officers, soldiers, and police in the infamous Katyn Massacre of 1940.66 The Soviets met serious resistance only in Finland, where the Finns held the far larger Red Army at bay for months, inflicting deep losses.67 Typically, Stalin referred to this period as “peaceful construction.”68

Stalin’s complacence didn’t last long, however. On the morning of June 22, 1941—less than two years since the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact—3,000 Panzer tanks rolled across the Russian border.69 Hitler had betrayed him.

Stalin’s Reign of Terror and Its Impact on the Soviet Union and Europe During WWII

Despite unmistakable warning signs and Soviet intelligence of Germany’s pending attack, Stalin refused to believe that Hitler would break the non-aggression pact. The purges had created a culture of fear and produced a military unwilling to act without Stalin’s specific orders. Stalin refused, even on the eve of the German attack, to allow the military to go on full alert and deploy to meet the pending invasion, despite the intelligence and defectors warning that Germany would invade early the next morning. Instead, Stalin gave no command other than to not provoke the Germans, and to execute one of the defectors for spreading disinformation. He then retreated to his dacha, drank, watched a movie, and went to bed.70 While Stalin slept, Germany unleashed an invasion on a massive scale: 3 million soldiers, 3,600 tanks, and 2,500 planes attacked Soviet cities and troop formations from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea.

Russia was completely unprepared. During the Great Terror, Stalin had murdered three marshals, 13 army generals, eight admirals, 50 army corps generals, 154 division generals, 16 army commissars, and 25 army corps commissars.71 Without experienced leaders, the Red Army was disorganized, allowing the German army to push as far as the outskirts of Moscow and Stalingrad on the Volga River. Military commanders, and even his inner circle, were terrified to wake Stalin with the shocking news, delaying any response for hours. Paralyzed, they even refused to allow the military to shoot at German aircraft bombing their cities and troops. On the first day, the Germans destroyed nearly 1,000 Soviet aircraft on the ground because Soviet generals were afraid to issue any order without Stalin’s approval. In the crucial first days of the invasion, “Operation Barbarossa” captured huge swaths of Soviet territory and killed or captured hundreds of thousands of Soviet soldiers, due to the military and civilian leadership’s fear of contradicting Stalin’s false view of reality.72

The German offensive failed, largely due to logistical difficulties in Russia’s harsh terrain and weather conditions. Hitler also underestimated the sheer tenacity of the Soviet troops, and their willingness to sustain losses and privation.73 Shortly after the invasion, the Soviet Union joined forces with the Allies. Although the Allies eventually emerged victorious, the USSR suffered an estimated 27 million total casualties during World War II, many due to communist incompetence and the absence of skilled military leadership.74 Between the Great Terror, the Communist Party’s poor management of the economy, and the new territorial conquests from the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet military was overextended and endured catastrophic casualties.

Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin at Yalta. Photo via NARA under the public domain.

Stalin’s Takes Central and Eastern Europe after the War

In February 1945, the Allies met at the Yalta Conference to discuss the post-World War II order. Stalin insisted on a buffer zone of “friendly” countries, and U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill agreed—with the condition that free elections be held in all Soviet-occupied territories. Stalin indeed held elections, but not before installing communists in key positions, typically through force and fraud. In Poland, the Soviets continued their campaign of repression and terror, constructing over 200 concentration camps for both civilians and soldiers.75 In Romania, Soviet troops disarmed the national forces and occupied their headquarters, from which they directed the Romanian king to appoint a communist as Premier.76 And so it continued: Similar puppet governments were imposed or “elected” in other Soviet-occupied nations, with varying levels of co-operation.77 These countries—soon called Soviet satellites—were all forced to adhere to communist principles: seizure and abolition of private property, elimination of basic freedoms such as speech and press, suppression of religion, and subjugation of national identity.78 When Stalin died in 1953, the Soviet Union had solidified communist control over much of Central and Eastern Europe, and communism was on the march in Asia.