Chapter 5

Vladimir Lenin and Communist Revolution

“He astonished all of us who were Marxists at the time with his tremendous knowledge of the works of Marx and Engels…For Lenin the teachings of Marx were a guide to action…The way in which Lenin worked over Marx is a lesson in how to study Lenin himself. His teaching is inseparably connected with the teaching of Marx, it is Marxism in action, it is the Marxism of the epoch of imperialism and proletarian revolutions.”

Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin’s wife and fellow revolutionary1

Lenin: Ideology in Action

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (1870-1924), better known as Lenin, was the architect of Russian communism and the driving force behind international communism and the world’s first totalitarian state. Lenin was born in Simbirsk, into a close-knit, comfortably middle-class family. He was not the first radical in his family: his elder brother, Alexander, was arrested and hanged in 1887 for plotting to assassinate Tsar Alexander III.2 Young Lenin briefly studied law at the Imperial Kazan University but was expelled for protesting school rules. Already radicalized by university and his brother’s death, Lenin became a devoted disciple of Marx’s writings and ideology. His sister Anna described him sitting by the kitchen stove, and “making violent gesticulations he would tell me with burning enthusiasm about the principles of Marxist theory and the new horizons it was opening to him.”3 Lenin eventually made his way to the Imperial capital of St. Petersburg, where he connected with Marxist groups and became influential in radical political circles.

Following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in 1917, Russia formed the liberal Provisional Government, which was transitional and weak. Lenin was not a man to waste an opportunity, and he and his Bolsheviks seized control of a capital in chaos, incited civil war, and forged the first communist nation along Marxist principles. Indeed, Marxist ideology became a powerful justification for claiming power by revolution, since it explicitly called for an all-out assault on every existing institution in government, society, and culture. But Marx had also predicted socialism as the inevitable next step after capitalism and before full communism in the historical process. Lenin recognized that Russia was not an advanced industrial economy like those Marx had targeted in Western Europe. Lenin also criticized the efforts of earlier Russian Social-Democrats as “slavish cringing before spontaneity” and too easily overwhelmed by bourgeois ideology.4 He argued for the creation of the “vanguard of the proletariat”—a small, elite group of professional revolutionaries—to lead the world socialist revolution and inspire true class consciousness in the rest of the proletariat.5

Building on Marxism, Lenin initiated a century and more of communist totalitarianism marked by deprivation, destruction, and violent death. His revolutionary vanguard, instead of inspiring class consciousness among workers, became a source of unrestrained despotism in the hands of Communist party elites in Bolshevik Russia and nearly 40 other countries.

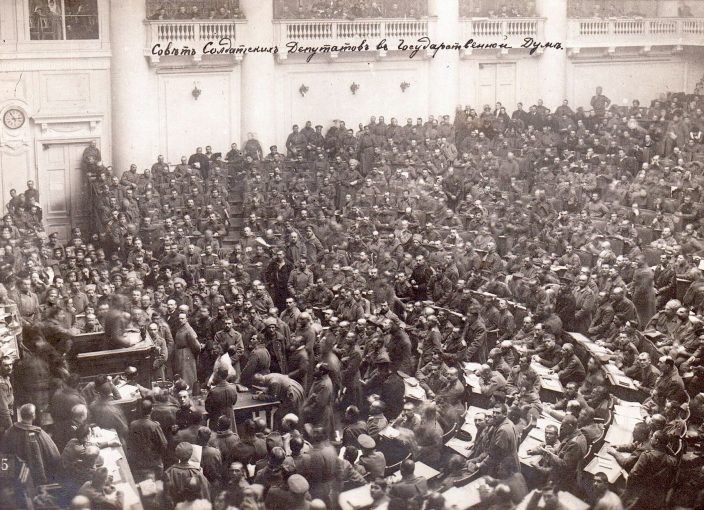

Bolshevik Party meeting, 1920. Photo via the public domain.

Seizing Power: The Russian Revolution

The seeds of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and Vladimir Lenin’s rise to power were planted three decades earlier in the 1880s, amid widespread social unrest. Tsar Alexander III (1845-1894) was a reactionary ruler whose instinct was to meet reform movements with repression, and his son and successor Tsar Nicholas II (1868-1918) agreed to minimal reforms under duress. In St. Petersburg, Lenin found like-minded Marxist groups calling for revolution to overthrow the tsarist autocracy. He became a leader of the revolutionary movement, traveling in Russia and Europe to meet other activists and to support strikes, all the while feverishly writing and translating. In late 1895, Lenin was arrested and jailed for 15 months; in 1897, he was exiled for three years to Siberia, but after his trip (in first class) was left free to write and agitate, and he subsequently moved to Europe.6

Discontent among the working classes in Russia boiled over on January 9, 1905 (January 22 in the Gregorian or Western Calendar), when a group of unarmed protesters made their way to the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg and demanded universal civil rights from Nicholas II.7 Authorities ordered the demonstrators to disperse as they approached the palace, but the protestors continued their march toward the Tsar’s residence. The Imperial Guard opened fire on the protestors, killing hundreds and wounding 1,500.8 Lenin was not troubled by the violence of what became known as Bloody Sunday; from the very beginning, he embraced terrorism and bloodshed as revolutionary necessities. From Geneva, a delighted Lenin wrote:

“The uprising has begun. Force against force. Street fighting is raging, barricades are being thrown up, rifles are cracking, guns are booming. Rivers of blood are flowing, the civil war for freedom is blazing up. Moscow and the South, the Caucasus and Poland are ready to join the proletariat of St. Petersburg.”9

The 1905 revolution, which included a wide range of factions and interests, failed to overthrow the Tsar, yet forced him to make several concessions. Unfortunately, reform was ineffective and insufficient, and came too late to satisfy many Russians. Ever more aggressive in his calls for revolution, Lenin also intensified his appeal for an alliance between the proletariat and the peasantry:

“We shall be traitors to and betrayers of the revolution if we do not use this festive energy of the masses and their revolutionary ardour to wage a ruthless and self-sacrificing struggle for the direct and decisive path. Let the bourgeois opportunists contemplate the future reaction with craven fear. The workers will not be frightened either by the thought that the reaction promises to be terrible or by the thought that the bourgeoisie proposes to recoil. The workers are not looking forward to striking bargains, are not asking for sops; they are striving to crush the reactionary forces without mercy, i.e., to set up the revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry.”10

Revolutionaries in St. Petersburg during the 1905 Revolution. Photo © IWM Q 81553.

Despite his contempt for the slow pace of reform under the Tsar, Lenin felt safe enough to return to Russia late in 1905. He was again forced into exile in 1907, continuing to agitate and write from abroad that “Marxist doctrine is omnipotent because it is true” and championing forces in society to “constitute the power capable of sweeping away the old and creating the new, and to enlighten and organize those forces for the struggle.”11

Russia’s entry into World War I in 1914 finally provided the crisis environment that Lenin needed for his revolution. The devastating human and economic costs of the war, which resulted in widespread shortages of food and other necessities, caused many Russians to grow weary of the conflict and their living conditions.12 Politicians in the Duma, Russia’s national legislative body, also turned against the royal family amid accusations of treason.13 In March 1917, a mutiny among a small group of troops in Petrograd (formerly St. Petersburg and still the Imperial capital) turned into a popular uprising. Lenin recognized this moment as an opportunity. His efforts in promoting and encouraging mutiny and desertions from the Army provided the armed muscle the Bolsheviks would later need to seize power and impose communist rule.14 Fearing these early riots would result in widespread mutiny, the Russian generals pressured Nicholas II to step down from power.15 Following the Tsar’s abdication, the Duma formed a new Provisional Government. Unappeased, the socialist elements of the February Revolution – the radical Bolsheviks and the somewhat more moderate Mensheviks – demanded that a soviet, or council of workers, be established to monitor the work of the legislature.16 This dual system of government proved horribly ineffective.

Lenin, still in exile, worked tirelessly to make his way back to Russia. He approached the German government to organize for him a safe passage to Petrograd. The German government was happy to help a known provocateur return to Russia: Lenin, they thought—correctly, as it happened–would be a powerfully destabilizing force in their great enemy to the east. Lenin was spirited home on a “sealed train,” so that he could claim never to have set foot on German soil.17 Germany even provided economic aid to him and the Bolsheviks upon his arrival in Petrograd.18 Once home, Lenin demanded the total dissolution of the Russian government and the creation of a socialist state. More moderate socialist groups, notably the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries, opposed Lenin’s demands.19 Lenin vehemently rejected calls for compromise and peaceful transition and mocked all “philistine conceptions of morality.”20 Although the Mensheviks were more popular with the Russian people, the Bolsheviks were the most organized, disciplined, and violent faction of the revolutionary movement, and Lenin was rapidly able to gain greater control of the floundering government.21 To the people, he promised “Peace, Land, and Bread,” but to his Bolshevik followers, Lenin promised violence and terror against anyone who opposed them.

In October 1917, the second wave of the Russian Revolution began, with Lenin’s Bolsheviks leading the charge. The Bolshevik Central Committee signed a decree in early October stating that “[a]n armed uprising is inevitable, and that the time for it is fully ripe.”22 Now Lenin reaped the fruits of his earlier efforts promoting mutinies and desertions among Army soldiers who no longer believed in the war and hated the new government. Russian soldiers and sailors joined the October Revolution, which, in reality, was a Bolshevik coup. The weak Provisional Government quickly lost control of the nation’s governing bodies and military.23 By October 26, just twenty-four hours after the coup began, the Winter Palace and Provisional Government fell to Bolshevik-led troops and workers’ militias, called Red Guards. Within months, these forces would become the Red Army.

Some of the first victims of Lenin and the Bolsheviks were the Tsar and his family. The royal family was placed under the control of Yakov Yurovsky, head of the local Cheka (secret police, focused largely on “political crimes”). He received orders from Moscow in July 1918 to inventory all the Tsar’s property, confiscate it, and then execute the entire family.24 On the night of July 16-17, Yurovsky ordered the Tsar, his wife and five children, their physician, and the family’s servants into the basement. The family was shot to death in a bungled, bloody execution.25 The Bolsheviks then stripped the bodies of any valuables, burned the corpses, poured sulfuric acid on the remains, and dumped the bodies in a shallow grave beside a road.26

With the Tsar dead, Lenin rapidly worked to consolidate power around his Bolsheviks. When a series of elections failed to give the Bolsheviks a clear victory, Lenin declared the elections illegitimate and counter-revolutionary.27 Wrote Menshevik founder, Fyodor Dan, “You want to hold on [to power] by means of internal war! But I ask you: in whose name are you doing it? In the name of the soviets? But you know that every new set of elections leaves you in the minority in the soviets!”28 Lenin expelled the opposition parties from the Central Executive Committee and put down the resulting strikes and protests by throwing rival leaders in jail and shooting protesters.29 The resulting civil war between the various communist factions (“Reds”) and the pro-monarchists (“Whites”) lasted six years and cost almost seven million lives.”30

The Petrograd Soviet Assembly, 1917. Photo via the public domain.

Economic Ruin and the Red Terror

During the Russian Civil War, Lenin pursued the same kind of total power that he once despised in the Tsar. Lenin’s first major policy victory came in March 1918 with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, an agreement with Germany that enabled Russia to withdraw from the First World War, freeing Lenin to focus his attention on internal power struggles. Though committed communists and revolutionaries, the Bolsheviks had no background in governing and running businesses, much less managing a national economy. Armed with their ideological certainty and undaunted by their lack of experience, the Bolsheviks immediately moved to nationalize industry, effectively taking total control of the world’s fifth largest economy.31 Economic ruin was the result. Casting about for cash to fund his new communist state, Lenin attacked and looted organizations, churches, and private individuals. The Bolsheviks nationalized the banks, taking bank managers hostage until they opened the vaults or met ransom demands, and confiscating the personal savings of anyone they considered rich or bourgeois.32

During the Civil War, the Bolsheviks worked to exert control over all economic production, particularly agriculture and industry. They nationalized foreign trade, but due to the war, Western blockades, and other economic issues, Bolshevik Russia was not producing anything of value to trade. To make matters worse, the communists did not want “capitalist infection” from abroad and they stopped most imports, worsening an already terrible economic situation.33 In 1918, Lenin and the Bolsheviks created the Supreme Council of the National Economy (VSNKh) to manage every enterprise and to regulate and organize all production and distribution. With private property abolished and a new economic bureaucracy in place, the state theoretically controlled all economic activity. “War Communism,” as it became known, nationalized all industry, forbade strikes, militarized forced labor, and rationed food.34

Despite widespread hunger and privation, party elites lived comfortably. Lenin himself was famously indifferent to creature comforts, and most of his inner circle lived austerely; however, communist officials lost no time in carving out special perks for themselves. Special shops, restaurants, and luxury train cars were available to government officials, as well as a system of grants, bonuses, and expense accounts.35 War Communism ensured adequate supplies for those deemed most essential—namely, the party power base and the military—by seizing the substance of the “counter-revolutionary” peasants.

The communists announced an official campaign of violence and terror against those who opposed them. Inspired by the Reign of Terror in revolutionary France–Lenin even raised a statue to Robespierre in Moscow36 –the Red Terror saw between 50,000 and 200,000 people killed.37 Daily lists of the executed were published in newspapers, along with vehement justifications of the forced labor camps and murders.38 Leading Marxist revolutionary and Red Army founding commander Leon Trotsky observed, “Terror can be very efficient against a reactionary class which does not want to leave the scene of operations. Intimidation is a powerful weapon of policy, both internationally and internally.”39 Anyone slow to submit to Lenin’s repressive, confiscatory policies was labeled a counter-revolutionary, and an enemy of the state. Those killed included not only loyalists and members of the White Army but also the clergy, Mensheviks, Socialist- Revolutionaries, and any workers or farmers who failed to meet their quotas.40 Lenin’s “Hanging Order” telegram is instructive:

Comrades! The uprising by the five kulak volosts must be mercilessly suppressed. The interest of the entire revolution demands this, for we are now facing everywhere the “final decisive battle” with the kulaks. We need to set an example.

1. You need to hang (hang without fail, so that the people see) no fewer than 100 of the notorious kulaks, the rich and the bloodsuckers.

2. Publish their names.

3. Take all their grain from them.

4. Appoint the hostages — in accordance with yesterday’s telegram.

This needs to be done in such a way that the people for hundreds of versts around will see, tremble, know and shout: they are throttling and will throttle the bloodsucking kulaks. Telegraph us concerning receipt and implementation.

Yours, Lenin.

PS. Find tougher people.41

Guards holding a banner that reads “Long live the Red Terror.” Photo via the public domain.

Lenin’s policies, Bolshevik incompetence, the Civil War, and crumbling civil society resulted in a great famine in 1921, during which 5 million died.42 The famine also provided Lenin an opportunity to win the coming confrontation between the communists and the Russian Orthodox Church, by blaming the church for doing little to relieve the famine.43 The Bolsheviks had already nationalized church property, but in February 1923 they ordered the confiscation of all church valuables, including those sacred objects used in rites of worship.44 The confiscation was met with resistance from the church and parishioners, who in turn were confronted with communist brutality. In the end, 28 bishops, 1,200 priests, and over 20,000 parishioners were killed or executed. The communists also stole 940 pounds of gold and 550 tons of silver, which barely covered a month of needed imports. And Lenin and the Bolsheviks achieved another communist goal: to destroy the last element of traditional Russian civilization, the Church.45 Like its French forebears, Russian communism sought to supplant traditional religion with its own ideology. Henceforth, only worship of the state would be allowed.46

Many peasants tried to resist the Bolsheviks through armed rebellion. Numerous peasant revolts erupted throughout the provinces, only to be brutally crushed by the Red Army.47 The increasingly repressive rule of the Bolsheviks even prompted reactions from urban workers and units in the Red Army. The most serious revolt took place in March 1921, when Red sailors and soldiers stationed in the port city of Kronstadt called for free elections, freedom of speech, and the freedom of the peasantry.48 The mutiny was crushed, and none of the demands were met.

It did eventually become clear that War Communism was unsustainable.49 The destruction wrought by years of devastating war and famine in Russia forced the Bolsheviks to loosen, temporarily, their drive toward collectivization and control. Faced with the enormity of transforming an overwhelmingly agricultural country into an industrialized state, Lenin had to adjust. Despite the formation in 1919 of the Communist International (Comintern), the promised international uprising also did not materialize, as the Red Army failed in its wars to spread communism to Poland and the Baltic states, two violent communist uprisings in Germany were put down, and the Hungarian Soviet Republic lasted only months before collapsing amid popular discontent and military pressure from Romania. Lenin acknowledged, “We know that so long as there is no revolution in other countries, only agreement with the peasantry can save the socialist revolution in Russia.”50 He approved a period of “breathing space” and “strategic retreat.”51 The economic component of this retreat, dubbed the New Economic Policy (NEP), allowed the establishment of small private businesses and permitted a free market in grain. While the NEP allowed the economy to recover slowly, many Bolsheviks, including Lenin himself, lamented that it only offered a “gradual path to socialism.”52 The concessions were purely pragmatic, and did not represent a major departure from the Communist Party’s brutal methods. As Lenin wrote in 1922, “It is the greatest mistake to think that NEP has put an end to terrorism. We shall yet return to terrorism, and it will be an economic terrorism.”53

Lenin’s Decline and Death

Lenin’s health deteriorated in 1922, and he relied on his onetime ally Joseph Stalin to execute key decisions; however, with his death imminent, Lenin began to question whether Stalin was the right man to succeed him. In a “testament” dictated on December 25, 1922, Lenin noted, “Comrade Stalin, having become Secretary-General, has unlimited authority concentrated in his hands, and I am not sure whether he will always be capable of using that authority with sufficient caution.”54 In a postscript dictated in early January 1923, he explicitly proposed finding a way to remove Stalin from his position. Lenin’s concerns were well-founded.

Lenin died in January 1924, and Stalin soon took control. He would rule the Soviet Union as dictator until his death in 1953, often using tools—such as the Gulag, the secret police, and the Red Army—created by Lenin himself.

The Marxist-Leninist Legacy

The two fathers of communism left the world a legacy of repression, deprivation, and death. Lenin adapted Marx’s communism to the history, culture, and circumstances of a Russia in turmoil in 1917.55 Where Marx had largely concerned himself with the urban proletariat, Lenin’s Russia featured far more peasant farmers than urban factory workers. This meant that Russia had not even reached the capitalist stage of development in Marx’s theory of history, but Lenin believed that his revolutionary vanguard could allow Russia to skip over the capitalist stage and proceed directly into communism. Always an avowed Marxist, Lenin was unwilling to wait for the “spontaneous” development of class consciousness according to what Marx saw as the necessities of history.56 Thus the political zeal and impatience of the Russian revolutionary merged with the radical ideology of Marx and Engels to become the most recognizable form of communism–Marxism-Leninism – and created the world’s first communist state. In Russia and the other countries overtaken by communist totalitarianism, more than a billion people would suffer under its despotic and deadly system of rule.