Chapter 4

Karl Marx

“Marx’s utterances were indeed full of meaning…but I have never seen a man whose bearing was so offensive and intolerable. To no opinion, which in the slightest degree differed from his, he accorded the honor of even a condescending consideration. Everyone who contradicted him he treated with the most abject contempt; every argument that he did not like he answered with biting scorn at the unfathomable ignorance that had prompted it, or with opprobrious aspersions upon the motives of him who advanced it. I remember most distinctly the cutting disdain with which he pronounced the word ‘bourgeois’; and as a ‘bourgeois’ that is, as a pitiable victim of the most depraved mental and moral tendencies, he pronounced everyone who dared oppose his opinions. Of course the propositions advanced or advocated by Marx in that meeting were throughout voted down because every one whose feelings had been hurt by his conduct was rather inclined to support everything that Marx did not favor.”

Carl Schurz, German Democratic Revolutionary who became a U.S. Senator1

Marx’s Rise as a Radical

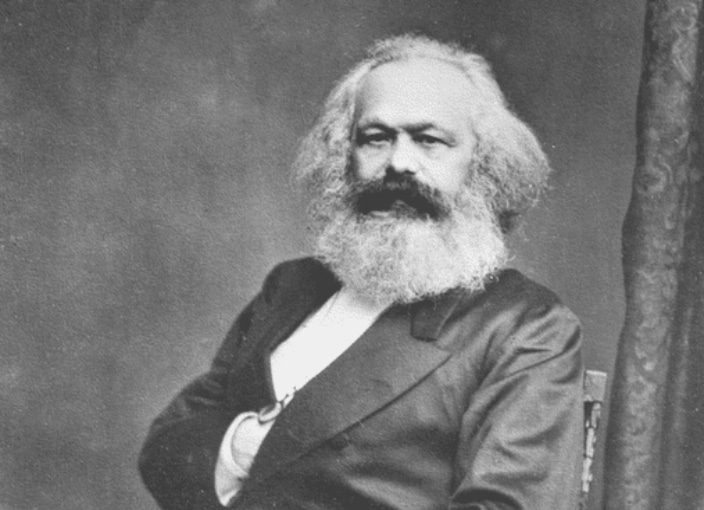

Karl Marx (1818-1883) — philosopher, journalist, historian, and father of the modern world’s bloodiest ideology — was born to liberal, middle-class parents in Trier, Prussia. As a young man, Marx attended a liberal high school where he wrote poetry and earnest Christian meditations.2 He then studied classics at the University of Bonn and engaged in such typical undergraduate activities as drinking, fighting, and running up debts. At his father’s insistence, Marx moved to the more academic University of Berlin to study law; however, he soon turned back to his real love — philosophy and poetry.3 While continuing his association with various anti-government political groups and poetry clubs, Marx joined the “Young Hegelians,” radical students of the German philosopher, G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831), whose dialectical model of history would inspire Marx’s own.4 Hegel was decidedly unpopular with the Prussian government, and Marx ran afoul of the traditional faculty at Berlin.5 Eventually, Marx had his dissertation accepted by the University of Jena, a more modern school with strong ties to Hegel and the German Romantic movement.

Since his political activities and association with the Young Hegelians (and perhaps his notoriously unpleasant personality) precluded an academic career, Marx began work as a journalist for Rheinische Zeitung, a radical newspaper that the Prussian government censored and banned after five months.6 Marx then moved to Paris to write for various other left-wing journals, and started his collaboration with his friend and financier, Friedrich Engels (1820-1895).7 Revolution was in the air, and by 1845 many European leaders had become alarmed at the various radical and conspiratorial groups operating on the continent. The French government moved to expel Marx that year at the request of the Prussian King, who was aware of Marx’s increasingly radical socialist and anti-imperialist views.8 Marx spent the next five years moving from city to city, library to library, before settling in London in 1850. During this time, Marx continued to refine his critique of capitalism and formulate his concept of “scientific socialism.”9

A portrait of Karl Marx by John Jabez Edwin Mayal. Photo via the public domain.

Scientific Socialism: Marx’s View of Man and Society

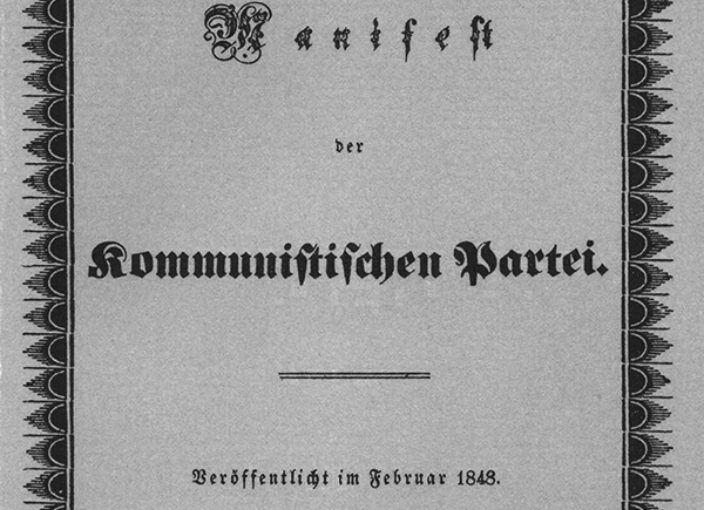

The later stages of the Industrial Revolution produced many critics of capitalism, and the socialist movement was gaining steam on the Continent and in Britain. In 1848, a year which saw popular protests and revolts sweep across Europe, Marx and Engels published the Manifesto of the Communist Party (more commonly known as The Communist Manifesto), outlining Marx’s radical ideology and calling for social, political, and economic revolution. Marx rejected other forms of socialism, particularly “utopian socialism,” which emphasized democratic ideals and equal rights in its plans for the reorganization of society.10 Rather, Marx argued that only “scientific socialism,” that is, a political method derived from what he saw as the socioeconomic outworking of historical processes, would be adequate to the task of achieving the emancipation of the working class.11 In fact, there was nothing scientific about it: Marx’s observations were academic, the product of time spent in libraries. Indeed, journalist and historian Paul Johnson observes that Marx reserved his most withering contempt for fellow activists with actual working-class roots and experience.12 More poet than scientist, Marx began with a vision and found facts to support it.13

Marx had a “materialist” conception of history, that is, he believed that material conditions and economic actions, not ideas, were the main drivers of change in society.14 He was particularly drawn to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, published in 1859, finding in the biologist’s approach a complementary materialist vision of development through conflict.15 Marx contended that economic forces alone form the base of society, upon which all other aspects of culture are constructed, and ultimately depend: “It is always necessary to distinguish between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production, which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the legal, political, religious, artistic or philosophic – in short, ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out.”16 In Marxism, the state or government is part of the superstructure built on top of the productive base.17

Like other socialists of his time, Marx viewed capitalism as an inherently flawed, exploitative, and oppressive socioeconomic system. Like them, Marx envisioned a perfect, classless, communist society. Unlike them, he believed that this new society would be achieved through revolution, not the gradual plans of the utopian socialists. As Engels fully appreciated: “For Marx was before all else a revolutionist.”18 Marx and Engels’s Manifesto did not conceal the violent nature of their ideological movement:

“The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win.”19

For Marx, the communist revolution justified taking control of society by force, eliminating all existing personal liberties as well as the traditional family and the religious, social, and political organization that formed the capitalist superstructure.

And all of this was global. Marx believed that history inevitably moves toward a final struggle resulting in world communism and that “[r]evolutions are the locomotives of history.”20 His communist revolution was meant to transcend borders, evolving and spreading, after first taking control in the most industrially advanced countries. The end of history would ensue after the international workers’ revolution. The state—as conventionally known—was then to “wither away” into a classless society.21 Instead, Marxist ideology generated vicious, repressive states characterized by violent death and profound human suffering. In Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Africa, Marx’s writings inspired communist revolutions and regimes in nearly 40 countries, leading to the deaths of over 100 million people and the suffering of many more.

A statue of Karl Marx. Photo by Hennie Stander via Unsplash.

Class Struggle – Oppressor Versus the Oppressed

Marx believed that different elements or classes of society were fundamentally pitted against one another, and that this class struggle was the driving force of all history. Marx urged the oppressed working class (the proletariat) to overthrow both its economic oppressors (the bourgeoisie) and their entire political, social, and economic system. As famously expressed in the Manifesto, “The theory of the Communists may be summed up in the single sentence: Abolition of private property.”22 Marx and Engels “traced the more or less veiled civil war, raging within existing society, up to the point where that war breaks out into open revolution, and where the violent overthrow of the bourgeoisie lays the foundation for the sway of the proletariat.”23 The Communist Manifesto called for the proletariat to seize all wealth and means of production, and to eradicate the bourgeoisie as a class.24 In theory, the revolutionary elites would then relinquish control to the workers in a perfectly egalitarian society; in practice, they entrenched themselves as a new, brutal ruling class that prioritized retaining power at any cost.

Marx’s Means to Achieve Communism

Marx and Engels called for the destruction of all aspects of the old bourgeois society by not only “civil war,” “open revolution,” and “violent overthrow” but also “despotic inroads on the rights of property.”25 The Manifesto identified ten measures that were critical to the communist revolution, especially in the most industrially advanced countries:

1. Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes.

2. A heavy progressive or graduated income tax.

3. Abolition of all right of inheritance.

4. Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels.

5. Centralisation of credit in the hands of the State, by means of a national bank with State capital and an exclusive monopoly.

6. Centralisation of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State.

7. Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State; the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands, and the improvement of the soil generally in accordance with a common plan.

8. Equal liability of all to work. Establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture.

9. Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of all the distinction between town and country by a more equable distribution of the populace over the country.

10. Free education for all children in public schools. Abolition of children’s factory labor in its present form. Combination of education with industrial production, &c., &c.26

Key to Marxism is the elimination of individual liberty and rights, including private property, as they exist in liberal democracies. Marx insisted that “none of the so-called rights of man, therefore, go beyond egoistic man, beyond man as a member of civil society – that is, an individual withdrawn into himself, into the confines of his private interests and private caprice, and separated from the community.”27 The idea of individual rights was part of the superstructure of capitalist society, and antithetical to his vision of human relations. For Marx and the communist regimes he inspired, individuals must be made to realize that their only value is in what they contribute to the collective. Marx rejected the very idea of human nature, seeing it as nothing more than a byproduct of material conditions. Establishing communism, therefore, would usher in a whole new kind of human being. Only then would each person labor cheerfully for the common good, and not for personal gain. Only then could the communists proclaim, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!”28

Marx was less interested in the specifics of governing, policy, and economics under his ideal society. He disdained the plans and projects of his rivals, seeing “the historical process as providing its own solutions,” such that socialists needed only “deliver the new world which the present now bears within its womb.”29 But the birth of communism was never natural. To “deliver” Marxism, communist rulers forcibly and violently destroyed and then remade societies, shedding blood and wrecking lives in the name of progress.30 Communism did not function as Marx had envisioned: it had to be not only imposed but sustained through violence and state repression.

Abolition of the Family and Religion

Marx saw the institutions of family, marriage, and religion as part of the capitalist superstructure that would be swept away by the new order. In lieu of marriage, Marx called for an “openly legalized community of women.”31 Marx claimed that marriage and the family were irrevocably tainted by capitalism; that, “bourgeois clap-trap” to the contrary, women and children had been reduced under capitalism to “mere instruments of production,” and that marriage in particular was simply another form of prostitution.32 All bourgeois social structures would be dismantled with the abolition of capitalist society: “The bourgeois family will vanish as a matter of course when its complement vanishes, and both will vanish with the vanishing of capital.”33

Following Young Hegelian Ludwig Feuerbach’s atheistic materialism, Marx viewed religion, too, as a byproduct of an exploitative system: “Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”34 In Marx’s worldview, material conditions determine spiritual ones: “It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.”35 Materialism rejects transcendence, acknowledging nothing beyond the physical world. Accordingly, Marx saw belief in God as a kind of coping mechanism, exploited by the bourgeoisie, for a working class in pain. If communism were established, he argued, religion would disappear as well.36 Only through communism could mankind achieve true happiness.37

Cover page of the Communist Manifesto. Photo via Wikimedia under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Marx’s Legacy and Victims

To his apologists, Marx was a radical visionary whose perceptive critique of capitalism led him to call for world revolution to remake society. Communism, like other forms of socialism, can seem attractive, especially to those living under imperialist, colonialist, or otherwise repressive conditions.38 But Marx’s ideology proved incapable of fixing the problems he identified without causing even greater suffering and injustice. In contrast to Marx’s prediction, communist governments have kept themselves in power as one-party bureaucratic states that trap their citizens in poverty and fear, and which use mass killing, imprisonment, and torture against those perceived as being a political enemy of the regime. These communist regimes have never functioned for the good of the masses, but only for the benefit of the totalitarian leadership and its ruling elite.

Despite Marx’s philosophical education and critique of elements of modern industrialization, his ideas were flawed by arrogance, intellectual dishonesty, oversimplification, and lack of practical experience. As ethical philosopher Peter Singer argues, “It isn’t far-fetched to suggest that his predictions have been falsified, his theories discredited, and his ideas rendered obsolete.”39 To date, Marxist ideology has failed to produce a communist utopia anywhere it has been attempted.40 Any theoretical appeal of Marxism stands in stark contrast to its actual historical record of bloodshed and repression.