Chapter 1

Chapter Sources

1. Victims of Communism, “Witness Project: Dan Novacovici”, October 17, 2019, video, 9:59, https://youtu.be/rA6igitW-zc.

2. For communist regimes being characterized by an official ideology, a one-party state, a monopoly on violence, control of information and mass media (books and movies included), and the use of a terroristic secret police to commit terror, see Carl Friedrich, “The Unique Character of a Totalitarian Society,” in The Great Lie: Classic and Recent Appraisals of Ideology and Totalitarianism, ed. Flagg Taylor (Wilmington, DE: Intercollegiate Studies Institute, 2011), 20-21. For information regarding communist regimes and their establishment of a government-planned and controlled economy, see Johann Arnason, “Communism and Modernity,” Daedalus 129, no. 1 (2000): 70, 73, 76, and 8; and Carl Joachim Friedrich and Zbigniew K. Brzezinski, Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy Second Edition (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965), 21-22.

3. “The Bill of Rights,” Amendments 1-10, from the National Archives and Records Administration, accessed November 3, 2021, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/bill-of-rights-transcript#toc-the-u-s-bill-of-rights-2. Spelling and punctuation reflect the original transcription from the National Archives website.

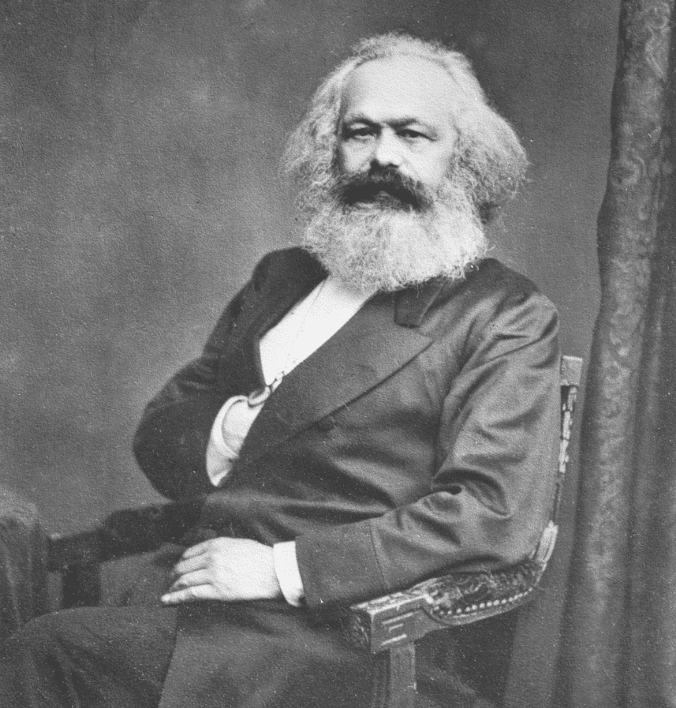

4. Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Steven Lukes, Stephen Bronner, Vladimir Tismaneanu, Saskia Sassen, and ed. Jeffrey Isaac, The Communist Manifesto (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 83 and The Communist Manifesto, The Marxist.org Archive, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch02.htm.

5. Ibid, 91-92. Spelling reflects the cited text.

6. Carl Friedrich, “The Unique Character of a Totalitarian Society,” in The Great Lie: Classic and Recent Appraisals of Ideology and Totalitarianism, ed. Flagg Taylor (Wilmington, DE: Intercollegiate Studies Institute, 2011), 20-21. See also Johann Arnason, “Communism and Modernity,” Daedalus 129, no. 1 (2000): 70, 73, 76, and 85.

7. Hannah Arendt, “Ideology and Terror: A Novel Form of Government,” in The Great Lie: Classic and Recent Appraisals of Ideology and Totalitarianism, ed. Flagg Taylor (Wilmington, DE: Intercollegiate Studies Institute, 2011), 20-21 and Johann Arnason, “Communism and Modernity,” Daedalus 129, no.1 (2000): 70, 73, 76, and 85.

8. Flagg Taylor, “Totalitarianism,” (speech, Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, September 8, 2021).

9. Sergey Nechayev, Catechism of a Revolutionary (London: Pattern Books, 2020), 2, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Catechism_of_a_Revolutionist/nCcvEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0&kptab=editions.

10. Vladimir Lenin, Speech in Memory of Y.M. Sverdlov,” Moscow March 18, 1919, from Lenin’s Collected Works, 4th English Edition, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1972 Volume 29, pages 89-94, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1919/mar/18.htm. This specific quote from Lenin is similar to Nechayev’s description of the “perfect revolutionary” in Catechism of a Revolutionary.

11. Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War (New York, NY: Pegasus Books 2007), 16, https://archive.org/details/russiancivilwar00evan/mode/2up?q=million.

12. Vladimir Lenin, State and Revolution (Russia: 1902), 81, 125, 130. For religious repression, see page 81; for repression of the freedom of press and assembly, see page 125; and for abolishing private property, see page 130. https://www.google.com/books/edition/State_and_Revolution/rl29BwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&kptab=overview&bsq=religion. See also Vladimir Lenin, What Is to Be Done (Russia: 1902) for restrictions on freedom of speech.

13. Isaac Deutscher, Stalin, A Political Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 1949), 7-9, https://archive.org/details/stalinpoliticalb00deut/page/n7/mode/2up.

14. Robert Service, Stalin, A Biography (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), 267.

15. David Hosford, Pamela Kachurin and Thomas Lamont, Gulag: Soviet Prison Camps And Their Legacy, Project of the National Park Service and the National Resource Center for Russian, East European and Central Asian Studies, Harvard University, 2 https://gulaghistory.org/nps/downloads/gulag-curriculum.pdf, and Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokin, The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 23-41.

16. Michel Ellman, “Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments,” Europe-Asia Studies 54, no. 7 (2002): 1155, https://www.jstor.org/stable/826310.

17. Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Thirties (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1968), 533 and Gill Elliott, The Twentieth Century Dead (London: Penguin Books, 1972), 223-24. Both Conquest and Elliot state Stalin is responsible for at least 20 million deaths. Anton Antonov-Ovseyenko, The Time of Stalin (New York: Harper and Row, 1981), 126. Antonov-Ovseyenko states Stalin killed between 30 and 40 million people. Stephane Courtois, et al., The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 159 and 186. Courtois estimates that at least 6 million individuals perished due to the famine under Stalin. Page 186 estimates that 2 million died in Gulag camps; however, Courtois claims that the Gulag deaths number is inflated. J. Arch Getty, Gabor Rittersporn, and Victor Zemskov’s “Victims of the Soviet Penal System in the Pre-war Years: A First Approach on the Basis of Archival Evidence,” American Historical Review 98 no. 4 (1993): 1017-1049 claims 1,053,829 citizens died in the Soviet camps from 1934 to 1953 not including labor colonies. Michael Ellman estimates that the number rises to 1.7 million Gulag deaths if labor colonies are included in “Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments.” For more on famine, see Davies and Wheatcroft, The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933, as they conclude that famine resulted in the deaths of 5.5 to 6.5 million. See also Stephen Wheatcroft, The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 414. Wheatcroft estimates that 3.6 million died because of the Soviet-caused famine. We have determined that 20 million is the best estimate based on available evidence.

18. Daniel Chirot, Modern Tyrants: The Power and Prevalence of Evil in Our Age (New York: The Free Press, 1996), 187.

19. Archie Brown, The Rise and Fall of Communism (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2009), 316-17, and Courtois, 495.

20. Frank Dikotter, The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History, 1962-1976 (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016), 183-91; Yongyi Song, “Chronology Of Mass Killings During The Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), SciencesPo, https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/document/chronology-mass-killings-during-chinese-cultural-revolution-1966-1976.html; and Lynn White, Policies of Chaos: The Organizational Causes of Violence in China’s Cultural Revolution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 7. This number has been highly debated. Lucian Pye’s “Reassessing the Cultural Revolution” The China Quarterly, no. 108 (1986): 597–612 claimed that 20 million died because of China’s Cultural Revolution. More recent accounts have argued that this number hovers around 1 to 3 million. For more see, Yang Su, Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 37.

21. Jonathan Fenby, Modern China: The Fall and Rise of a Great Power, 1850-Present (New York: Ecco Press, 2008), 351.

22. Kathyrn Weathersby, “The Soviet Role in the Early Phase of the Korean War: New Documentary Evidence,” The Journal of American-East Asian Relation Studies 2, no. 4 (1993): 5-6, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23613018. Prior to accessing the newly released archival evidence from the Soviet Union in the 1990s, many had argued that Stalin ordered North Korea’s invasion of South Korea. Ultimately, this new evidence reshaped many historians’ arguments as these documents revealed that Kim Il Sung was central to planning and executing the invasion, with Stalin’s support.

23. Max Hastings, The Korean War (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987), 128-40.

24. Bruce Cummings, The Korean War: A History (New York: Modern Library, 2011), 35. This number is still being debated as James McGuire’s Wealth, Health, and Democracy in East Asia and Latin America estimated 3 million total deaths and 1 million civilian deaths.

25. Courtois, et al., 564. It is difficult to provide concrete data on this number since the information has been kept secret by North Korea; however, this is a lower-end estimate.

26. Balazs Szalontai, “Political and Economic Crisis in North Vietnam, 1955-1956,” Cold War History 5, no. 4 (2005): 401, https://tinyurl.com/3fnhxa86.

27. Hirschman, Charles, Samuel Preston, and Vu Manh Loi, “Vietnamese Casualties During the American War: A New Estimate,” Population and Development Review 21, no. 4 (1995): 783–812, https://doi.org/10.2307/2137774.

28. Porter, Gareth, and James Roberts, review of Creating a Bloodbath by Statistical Manipulation, by Jacqueline Desbarats and Karl D. Jackson, Pacific Affairs 61, no. 2 (1988): 303–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/2759306.

29. World Peace Foundation, “Cambodia: U.S. bombing and civil war,” August 7, 2015, https://sites.tufts.edu/atrocityendings/2015/08/07/cambodia-u-s-bombing-civil-war-khmer-rouge/#_ednref9.

30. Ben Kiernan, “The Demography of Genocide in Southeast Asia: The Death Tolls in Cambodia,” Critical Asian Studies 35, no. 4 (2003): 586, https://doi.org/10.1080/1467271032000147041. This number is debated; the consensus is in the range of 1.5-3 million deaths from the genocide. See also “Cambodia.” University of Minnesota Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 2021, Accessed November 3, 2021, https://cla.umn.edu/chgs/holocaust-genocide-education/resource-guides/cambodia.

31. Stephane Courtois, et al., 647-655.

32. Jeffrey Dixon and Meredith Sarkees, A Guide to Intra-state Wars: An Examination of Civil, Regional, and Intercommunal Wars, 1816-2014 (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2015), 70. For information on Cuba’s authoritarian regime, see Darren Hawkins, “Democratization Theory and Nontransitions: Insights from Cuba,” Comparative Politics, 33, no. 4 (2001): 441-461, https://doi.org/10.2307/422443.

33. Stephane Courtois et al., 656.

34. Ibid., 664.

35. Haig A. Bosmajian, “A Rhetorical Approach To The Communist Manifesto”, The Dalhousie Review, 457. https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/62745/dalrev_vol43_iss4_pp457_468.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

36. Allan Wildman, The End of the Russian Imperial Army: The Old Army and the Soldiers’ Revolt (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980), 79.

37. Sean McMeekin, The Russian Revolution: A New History (New York: Basic Books, 2017), xii.

38. Yael Ronen, Transition from Illegal Regimes under International Law (Cambridge, Mass: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 16.

39. Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 99-103.

40. Jean Lopez, World War II Infographics (NY: Thames and Hudson, 2019), 149. See also National World War II Museum Online Exhibit “Research Starters: Worldwide Deaths in World War II,” National World War II Museum, accessed 9/27/21, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/students-teachers/student-resources/research-starters/research-starters-worldwide-deaths-world-war.

41. Joseph Stalin, Speeches Delivered at Meetings of Voters of the Stalin Electoral District, Moscow (Moscow: Foreign languages Publishing House, 1950), 19-40. Cited in http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1947-2/cold-war/cold-war-texts/stalin-election-speech/.

42. Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin’s Wars: From World War to Cold War (CT: Yale University Press, 2006), 245.

43. Michael Lynch, The Chinese Civil War, 1945-1949 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2010), 91.

44. Melvyn Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 2: The Calm Before the Storm: 1951-1955 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 21.

45. Jonathan Fenby, Modern China: The Rise and Fall of a Great Power, 1850 to the Present (Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign, 2008), 351.

46. Juliana Pennington Heaslet, “The Red Guards: Instruments of Destruction in the Cultural Revolution,” Asian Survey 12, no. 12 (1972): 1032–47. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2643022

47. Lu Xiuyuan, “A Step Toward Understanding Popular Violence in China’s Cultural Revolution,” Pacific Affairs 67, no. 4 (1994): 533–63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2759573

48. Frank Dikotter, The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History, 1962-1976 (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016), 183-191; Yongyi Song, “Chronology Of Mass Killings During The Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), SciencesPo, https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/document/chronology-mass-killings-during-chinese-cultural-revolution-1966-1976.html; and Lynn White, Policies of Chaos: The Organizational Causes of Violence in China’s Cultural Revolution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 7. This number has been highly debated. Lucian Pye’s “Reassessing the Cultural Revolution” The China Quarterly, no. 108 (1986): 597–612 claimed that 20 million died because of China’s Cultural Revolution. More recent accounts have argued that this number hovers around 1 to 3 million. For more see, Yang Su, Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 37.

49. Pawel Sasanka, “Poznan 1956: A Revolt That Shook the System,” polishhistory.pl, 2021, https://polishhistory.pl/poznan-1956-a-revolt-that-shook-the-system/. The Polish citizens’ complaints encompassed everything. “Regardless of where they lived and what industry they worked in, the attitudes of the workers were shaped by such aspects as elevated production quotas, low wages, dreadful health and safety conditions, difficulties in obtaining supplies, dramatic housing conditions, arrogance, hypocrisy, and corruption on the part of government officials, terror, brutal suppression of the Church, and Poland’s dependence on the Soviet Union.”

50. Ibid.

51. Mark Kramer, “The Soviet Union and the 1956 Crises in Hungary and Poland: Reassessments and New Findings,” Journal of Contemporary History 33, no. 2 (1998): 210, https://www.jstor.org/stable/260972.

52. Hope Harrison, Driving the Soviets up the Wall: Soviet-East German Relations, 1953-1961 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003), 240.

53. Ibid., 188.

54. Ibid., 192.

55. Jitka Vondrova, “Prague Spring 1968,” Academic Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, (2008), http://abicko.avcr.cz/2008/4/04/prazske-jaro-1968.html.

56. Matthew Quimet, Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 34-37.

57. Guenter Lewy, America in Vietnam (Cary, NC: Oxford University Press, 1980), 451.

58. Nghia M. Vo, The Bamboo Gulag: Political Imprisonment in Communist Vietnam (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Publishers, 2015), 101.

59. Noor Ahmand Khalidi, “Afghanistan: Demographic Consequences of War, 1978-1987,” Central Asia Survey 10, no. 3 (1991): 101 and 107, http://www.nonel.pu.ru/erdferkel/khalidi.pdf.

60. James Felak, “Polish Communist Perspectives on John Paul II: The Pope’s 1979 Pilgrimage to Poland in State, Party, and Police Documents,” The Polish Review 66, no. 1 (2021): 25, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/polishreview.66.1.0025.

61. Dennis Dunn, There Is No Freedom Without Bread! 1989 and the Civil War That Brought Down Communism, (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2009), 85.

62. James Felak, “Polish Communist Perspectives on John Paul II: The Pope’s 1979 Pilgrimage to Poland in State, Party, and Police Documents,” The Polish Review 66, no. 1 (2021): 25, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/polishreview.66.1.0025.

63. Michael Gehler, Piotr Kosicki, and Helmut Wohnout, Christian Democracy and the Fall of Communism (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2019), 203.

64. Sorin Antohi and Vladimir Tismaneanu, Between Past and Future: The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Aftermath (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2000), 90.

65. Courtois et al., 4. See also Benjamin Valentino, Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century (New York: Cornell University Press, 2004), 91.

66. Angus Maddison, “The World Economy,” Development Center of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2006): 184-185 https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~aldous/157/Papers/world_economy.pdf.

67. The World Bank, accessed 10/1/21, https://www.worldbank.org/en/home. VOC reviewed the populations of communist nations and added them together to find that over 1.5 billion citizens still live under this regime.

68. Rebecca Wright, Ivan Watson, and Ben Westcott, “Ugyhurs in Xinjiang are being given long prison sentences. Their families say they have done nothing wrong,” CNN World, August 1, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/06/24/china/xinjiang-prisons-china-intl-hnk-dst/index.html.

69. Department of State, “2021 Trafficking in Persons Report: North Korea,” accessed 10/5/21, https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-trafficking-in-persons-report/north-korea/. For Cuba see Department of State, “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Cuba,” March 30, 2021, https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/cuba/.

Explore the curriculum

Introduction to Communism

What is Communism, how is it implemented and maintained, and what are its effects on religion?

The fathers of Communism

Learn about the lives, the crimes, and the global influence of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin.

Stalin and the Soviet Union

Examine Joseph Stalin’s rise to power, his brutal rule, and the legacy of the Soviet Union.